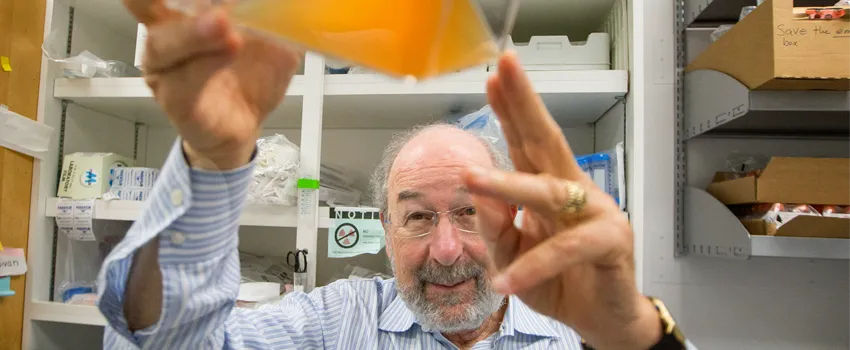

Photo by Norbert von der Groeben: Dr. Ronald Levy.

Stanford Medicine Scope -April 1st, 2016 - by Lindsey Baker

About two months into my uncle’s first round of chemotherapy, he began to experience a slew of awful side effects. Neuropathy made it impossible for him to play guitar. Nausea rendered food – one of his great passions – practically inedible, and he struggled to keep on weight. And newly developed skin lesions caused him pain.

He had been prepared for the fatigue, hair loss and general malaise that often accompanies chemo, but he was taken aback by the severity – and diversity – of the side effects.

Chemotherapy has been the gold standard of cancer treatment since its discovery in the 1940s – and for good reason. It’s saved countless lives and has provided important treatment options for patients. But the way it works – by attacking all cells, both healthy and diseased, can wreak havoc on the body.

Today, scientists are on the lookout for new treatments. Two lines of research show particular promise: immunotherapy, which harnesses the power of the immune system to seek out and destroy tumors; and targeted therapies, which can reverse the effects of cancer-causing genetic mutations.

Both have gained traction in recent years, and are already changing the cancer therapy paradigm. But Stanford oncologist Ronald Levy, MD, and his colleagues wondered what would happen if they combined these two lines of attack.

While immune therapies are effective in only some patients, they can lead to long-term remissions. Targeted therapies, on the other hand, usually cause short-term improvements, but work in more patients.

“We thought that putting the two together had the potential to get the best of both worlds,” explained Levy in an article on the Department of Medicine website.

So the team launched a preclinical study using anti-PD-L1 antibodies, an immunotherapy, together with the targeted drug ibrutinib. And they found that when combined, the drugs were even more effective.

In mice with lymphomas, breast cancers and colon cancers, the combination of anti-PD-L1 and ibrutinib shrank tumors and cured the animals. Even in cancers that didn’t respond to either drug alone, the combination yielded positive results, and the drug combination successfully taught the animals’ immune systems how to fight off the cancers in the future.

Now, Levy’s team will launch clinical trials of the drug combinations in humans; seven trials are already in progress, including two that are based at Stanford.

“I think this it the future of cancer therapy,” Levy said. “I hope this will allow us to replace chemotherapy and all those bad side effects that they cause.”

My uncle and I do, too.