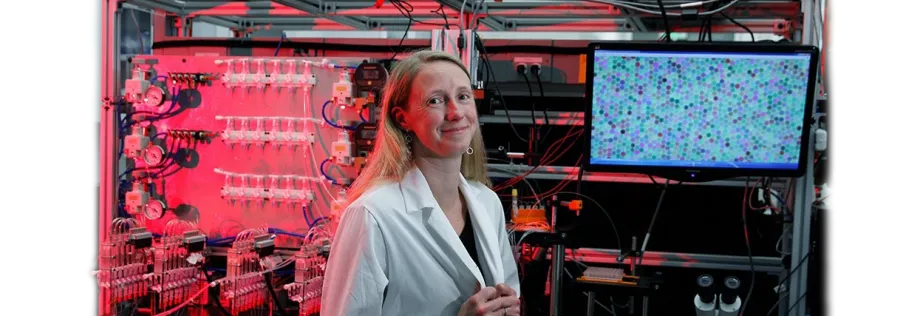

Photo by Paul Sakuma: To better study how proteins recognize their binding partners, Polly Fordyce's lab creates tiny, specially designed beads that are marked with different colors. Different peptides are glued to the beads' surfaces and then mixed with the protein being studied. The screen to Fordyce's right displays an image of the beads.

Stanford Medicine News Center - March 6th, 2017 - by Yasemin Saplakoglu

When faculty member Polly Fordyce was 6, she liked to take a journey across 40 orders of magnitude.

Her father, who worked for NASA at the time, would take her to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., where together they would watch a 1977 short film called Powers of Ten.

The film begins with a couple having a picnic at a lakeside park in Chicago. An overhead view zooms out so that every 10 seconds, the scene appears another 10 times farther away from the starting point. The viewer is swept from the park to the country, to the blues and greens of Earth seen from space, and then out beyond the galaxy. Then the scene zooms back in and travels even deeper, into cells, inside a protein and finally to an atom — a range of 40 orders of magnitude.

Fordyce, PhD, an assistant professor of genetics and of bioengineering, describes her younger self as a dorky kid who preferred staying inside during recess solving math problems to facing the indignities of being picked last for sports. She liked to think about different length scales at an early age.

Now, she delves deep into the body to help researchers understand disease. She develops new technology to accelerate the process of studying proteins. In the past, researchers were unable to predict which molecules interacted with which proteins in the body, and so they had to test the possibilities one by one. Today, Fordyce’s technology allows them to predict and narrow down the number of targets they need to test.

“We don’t study specific diseases; we try to make tools that we can apply toward understanding many different diseases,” said Fordyce, who is also a member of Stanford Bio-X and Stanford ChEM-H.

‘Socially awkward’

Fordyce was born and raised in Washington, D.C. “I wish I could say that as a kid I showed some particular talent for anything beyond being socially awkward,” she said. “But I didn’t really distinguish myself in any way until I returned to college after taking some time off and discovered physics and biology.”

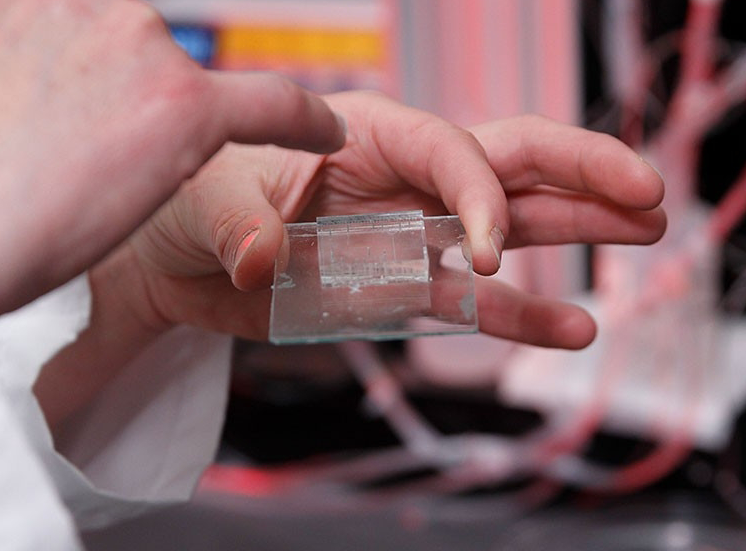

Photo by Paul Sakuma: Fordyce examines a microfluidic device

that is used for developing the tiny beads.

She double-majored in physics and biology at the University of Colorado-Boulder. Shortly after, she came to Stanford to pursue graduate studies in physics in the laboratory of Steven Block, PhD, a professor of applied physics and of biology. While in Block’s lab, she worked as part of a team that developed new microscopes for applying force to molecules and understanding how it affected their movements. “The idea of coming up with new ways to visualize interactions at tiny length scales invisible to us was something I quickly became very interested in,” she said.

As a postdoctoral scholar in the lab of professor Joe DeRisi, PhD, at UC-San Francisco, she worked on developing microfluidic tools for genomics, which she describes as a way to “shrink down biology.”

Fordyce joined Stanford’s faculty in 2014 and now has her own lab, where she and her research team delve many orders of magnitude deep into the body, looking at 1,000 reactions at once, to study how proteins recognize their binding partners. Half of her lab focuses on microfluidic devices and the other half on beads made by those devices.

“There used to be a TV show in the ’80s that was called 3-2-1 Contact,” Fordyce said. “And its theme song went something like” — she started to sing — “‘contact is the answer is the reason for everything that happens.’” That’s the same with proteins in the body — their interaction is key to understanding a lot of different processes, she said.

Microfluidic devices drive the research in Fordyce’s lab. These small devices have channels embedded in them, each the size of a human hair. Their advantage, according to Fordyce, is that they allow researchers to do biological experiments using only a small amount of material.

Tiny, colored beads

In October 2016, Fordyce received a five-year New Innovator Award from the National Institutes of Health for her team’s work on a unique project. Using microfluidic devices, her lab develops tiny, specially designed beads made of polyethylene glycol diacrylate, a polymer, with luminescent nanoparticles inside them. The beads are 40 to 50 microns in diameter — smaller than the thickness of a sheet of paper. The researchers mark the beads with different colors — over 1,000 in total — and glue diverse peptides, the building blocks of proteins, onto their surfaces. Then they mix them in a test tube with a protein they want to learn about.

Photo by Paul Sakuma: Fordyce chats with graduate student Kara

Brower and postdoctoral scholar Adam White, who are members

of her lab.

The point is to observe which peptides the protein of interest binds to the strongest and which ones it just isn’t attracted to — information that is necessary to develop therapeutics for a variety of diseases, according to Fordyce.

“The only way we can test 1,000 peptides is if we encode the beads in some way to tell which peptide is on which bead,” Fordyce said. “The colors are the codes.”

There’s just one problem: The protein is microscopic, so once it binds, it’s impossible to tell which peptides it has bound to.

So, the team throws in labeled antibodies — fluorescent proteins that bind specifically to the protein of interest. “The labeled antibody is like a reporter that allows us to understand what is happening on the microscale,” Fordyce said. First, they image the mixture with ultraviolet light to excite the luminescent nanoparticles and figure out which peptide sequences each bead has. Next, they shine visible light onto the mixture to observe how much antibody is bound to the beads. The combination of these two imaging techniques allow them to deduce which peptides the protein binds to and at what intensity.

What they end up with is a bunch of pictures that show which colored bead is bound to the protein of interest.

“In the same time it takes somebody to measure one thing, now we measure 1,000 things, and that drives science forward 1,000 times faster,” Fordyce said. “If we were to do these experiments with traditional biochemistry techniques, it would take years and armies of postdocs.”

Custom microscopes

“It’s really hard to make 1,000 different colors and then be able to tell 1,000 different colors apart,” Fordyce said. To do that, her team built custom microscopes, microfluidic devices and software to run all the instruments.

Fordyce and her team made much of their lab equipment from scratch. They took apart certain parts of commercial microscopes and 3-D-printed other parts to create a custom microscope capable of imaging the colored beads with deep UV light.

As a first application of this technology, Fordyce is collaborating with Martha Cyert, PhD, a professor of biology at Stanford whose lab focuses on understanding calcineurin, a protein known to activate the immune system.

“Polly goes beyond being energetic,” Cyert said. “She is a force of nature.”

Common post-transplant drug therapies target calcineurin to dampen the immune response. However, the protein has many roles throughout the body, so patients receiving these drugs also experience many unwanted consequences. Now, Cyert is working with Fordyce’s lab on a project aimed to identify all the proteins calcineurin binds to — not just those in the immune system — by tagging every colored bead with a different human peptide.

“The new peptide-bead technology that Polly developed will revolutionize how we study protein-based information networks within cells,” Cyert said.

Investigating protease interactions

About two months ago, Fordyce also began collaborating with Matthew Bogyo, PhD, a Stanford professor of pathology. Proteases are enzymes that function by cleaving other proteins and are prominent player in many human diseases, most notably cancer; in cancerous tissue, there is an increase in protease levels. Bogyo’s lab is developing fluorescent probes that light up when interacting with proteases so that when a patient is imaged, it is possible to see where diseased tissues, like cancer, are located. The lab is using Fordyce’s bead technology to help rapidly screen large pools of peptides to find those that produce a fluorescent signal when cleaved by proteases.

“Polly’s technology has huge potential for us to search for new protease substrates at ‘powers of 10’ greater diversity than we would be able to do if we had to test each substrate individually,” Bogyo said. “It could be a game changer for our work.”

The other half of her lab also uses microfluidic devices, but without the portability of the beads. These devices each have 1,000 different chambers that can run 1,000 different reactions at once. Although the point is again to accelerate the speed of experimentation, these devices can also reveal information about reactions that the beads would miss. Whereas experiments with the beads look at single mechanical interactions between proteins, these devices can look at entire chemical reactions without missing weak ones or products that diffuse away.

Fordyce was also recently named an investigator at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, a nonprofit medical research organization aimed at developing the tools to cure, prevent or manage all disease. As an investigator, she will receive up to $1.5 million over five years to support her work.

When she’s not in the lab, Fordyce likes to get outside. She loves to rock climb and explore the outdoors with her husband and their 4-year-old twin daughters.

When she’s in the lab, she gets sucked into the wonder of different scales. “We use tools on the micron scale to understand molecular interactions on the nanometer scale which actually explain behavior on the organismal scale,” Fordyce said. “It’s pretty amazing.”