Photo by UGREEN 3S, Shutterstock.

Stanford Medicine Scope - April 11th, 2017 - by Christopher Vaughan

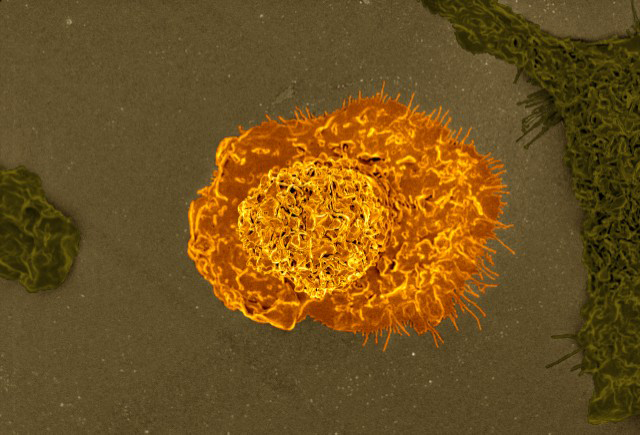

In recent years, scientists in the laboratory of Stanford’s Irving Weissman, MD, discovered that cancer cells cover themselves in copies of the CD47 “don’t eat me” protein to protect themselves from being engulfed and devoured by immune cells called macrophages (shown at right). But it was never clear how cancer cells increased the production of CD47.

Photo by NIAID: Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a macrophage.

Now, Weissman and his colleagues have discovered that cancer cells accomplish this trick by recruiting molecular pathways usually used for inflammatory processes. One particular pathway involves a protein called tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha), which is produced in response to infection or trauma. It attracts and activates macrophage cells, which destroy sick or damaged cells. Ironically, that same genetic machinery is being used by cancer cells to protect themselves from those macrophages. The researchers published a paper describing the research in the journal Nature Communications.

“Usually TNF-alpha is involved in attracting immune cells to tissues that need to be healed,” said Paola Betancur, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Weissman lab and first author on the paper. “But in this case, the tumor is using the same inflammatory mechanisms to protect itself by increasing CD47 production.”

The researchers found that TNF-alpha stimulates transcription by binding to a genomic region associated with the CD47 gene known as a “super-enhancer.” Tumor cells can evolve super-enhancers by leaving more of their DNA free for multiple transcription factors to bind, resulting in a kind of critical mass that markedly increases the production of the associated protein.

“By mapping enhancers, we showed that each cancer can lock in the permanent increase in CD47 production by turning enhancers into super-enhancers,” said Weissman, who is director of the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine and the director of the Stanford Ludwig Center for Cancer Stem Cell Research and Medicine.

The team then tested possible anti-cancer therapies. After implanting human breast cancer samples into mice, they treated the breast tumors with antibodies to TNF-alpha and/or to CD47, with the goal of triggering an immune attack. Since both these mechanisms can decrease the amount of CD47 “don’t eat me” signal that the macrophages see, using both antibodies together should boost the anti-cancer activity of the immune system, which is exactly what the scientists saw. The team now plans to test if this strategy works with other kinds of cancers.