Graphic by Ralwel, Shutterstock.

Stanford Medicine Scope - May 18th, 2017 - by Cameron Scott

Heart disease continues to be the largest single cause of death in the United States and worldwide. But familiarity seems to breed contempt.

Most American adults don’t have their cholesterol or other risk factors checked regularly, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And when those who do see dangerously high numbers, many just sigh and vow — again — to eat better and exercise more.

It’s as if we’ve accepted heart disease as inevitable. But Joshua Knowles, MD, an assistant professor of cardiology in the School of Medicine, argues that it is not. He’ll make his case in a Health Matters presentation on the Stanford campus on May 20.

Consider this: People with lifelong low LDL cholesterol (the “bad cholesterol”) have rates of heart attack and stroke that are a whopping 90 percent lower than our own, according to a recent study of an Amazonian tribe.

The tribe, who eat mainly fish and fruits and vegetables and have physically active lives, have average LDL levels similar to those found in newborns: about 50 mg/dl. In American adults, the average LDL level is 120 mg/dl, and many have much higher levels. It doesn’t have to be this way, Knowles says.

Of course, many of us have a hard time resisting a juicy bacon cheeseburger on the weight of hypotheticals. And other risk factors, such as genetics and age, lie completely beyond our control. Even so, Knowles still doesn’t think we are doomed to suffer from heart disease.

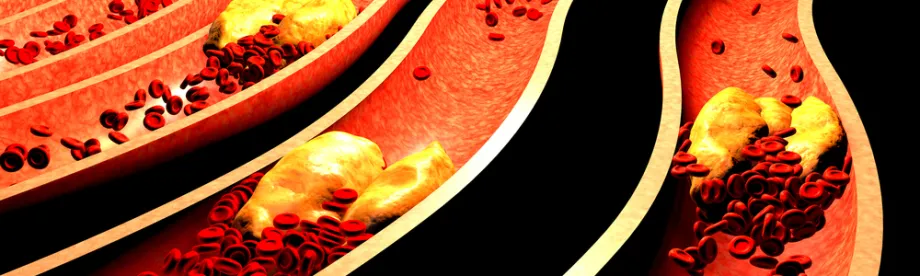

Medications can help contain, or even roll back, cardiovascular risk we have already taken on — in the form of cholesterol plaque deposited in the arteries — before we ever see a worrisome lab result.

Statins, a class of cholesterol-lowering drugs, have made it easier to lower LDL cholesterol since they were first prescribed in 1987. The drugs lower blood LDL levels by interfering with the body’s ability to make the fat-protein hybrid.

Newer research suggests that statins may also change the makeup of plaque already in the arteries so that bits are less likely to break off. (It’s this plaque rupture that can dam up an artery and trigger a heart attack or stroke.) While past generations of doctors thought plaque was plaque, newer approaches differentiate between stable and dangerously unstable plaque deposits.

In 2015, a new class of cholesterol drugs, called PCSK9 inhibitors, presented a second line of defense for very high-risk patients who can’t get their bad cholesterol levels into the low-risk range with statins alone. PCSK9 inhibitors, like evolocumab, ramp up the body’s ability to metabolize cholesterol so it isn’t deposited as plaque.

According to new studies, including this 2016 paper in JAMA, PCSK9 inhibitors may also eat up some existing plaque, giving patients for the first time the chance to clear out the ghosts of hamburgers past.

“For most of us, genetic risk is not destiny, and a lifetime of healthy living can combat genetic and inherited risk,” Knowles told me. “And when lifestyle is not enough, new drugs like PCSK9 inhibitors on top of statins offer a good chance to prevent bad outcomes.”

Knowles will talk to Health Matters attendees about how to control modifiable risk factors like high cholesterol, blood pressure, smoking, and stress and sleep patterns. The event is free and open to the public, and a video of his talk will be available in coming weeks.