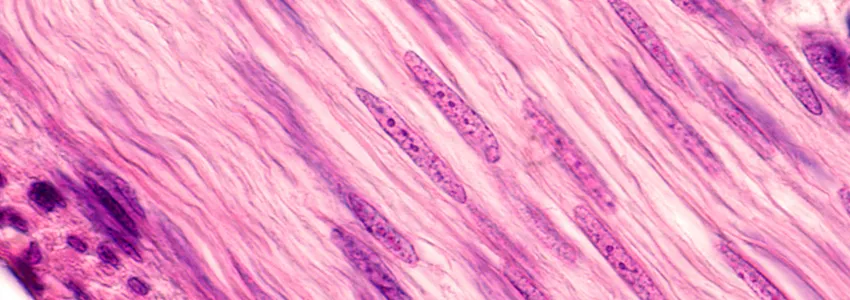

Image by Jose Luis Calvo, Shutterstock.

Stanford Medicine Scope - June 20th, 2017 - by Krista Conger

I’ve been writing a lot recently about ways to tinker with muscle stem cells to encourage them to repair muscles injured by overuse or trauma. But what about when muscle is missing completely? Major traumatic events such as landmine explosions can rip away whole chunks of tissue and make it difficult or impossible to ever regain function. In the face of such complete devastation, even muscle stem cells falter.

Now Stanford neurologist Thomas Rando, MD, PhD, and former postdoctoral scholar Marco Quarta, PhD, have outlined a three-part approach that, at least in mice, helps muscle stem cells grow new muscle tissue. They published their results today in Nature Communications.

As Rando, who also directs Stanford’s Glenn Center for the Biology of Aging, described to me in a phone conversation:

Big, traumatic wounds like those experienced by some veterans are very difficult to treat clinically. Usually the primary focus is on repairing damage to the skin and bone. We haven’t been able to do much to encourage regrowth of the missing muscle. Injecting muscle stem cells doesn’t work because they don’t function well in a vacuum.

So what to do? Rando and Quarta built on earlier work in which they showed that muscle stem cells are happiest when they feel at home. In their previous study, they mimicked the stem cells’ environment by constructing artificial muscle fibers upon which to grow the stem cells in the laboratory. In this new study, they created a three-dimensional structure called a bioscaffold — basically a muscle fiber in which the naturally occurring cells are removed to leave behind just the extracellular matrix. Muscle stem cells seeded upon the matrix snuggled in and, when transplanted into mice, began to replace missing muscle tissue. But then they took the “home away from home” concept one step further.

“We found that if we included other cells from muscle tissue such as endothelial and blood cells, we significantly improved the ability of the muscle stem cells to engraft and make new muscle,” Rando explained to me. “In other words, the bioscaffold gives them the architecture they need, but they do even better when surrounded by familiar neighbors.”

But although the muscle stem cells were performing admirably, Quarta and Rando noticed that the new muscle fibers that were being created were poorly connected to the animals’ nervous systems. This compromised the function of the new muscle tissue, hampering its strength and responsiveness. However, animals that were exercised after receiving the cell-seeded bioscaffold in areas of missing muscle recovered much better.

According to Rando:

When the nervous system that controls muscle contraction is disrupted, the nerves have to regrow into the new muscle. We found that exercising the animals significantly enhanced the speed and effectiveness with which the nerves grow back. This is very interesting because there is currently a debate as to how to handle musculoskeletal injuries in humans. Is activity after surgery beneficial, or harmful? If beneficial, what are the parameters? When should the activity start?

The researchers conducted most of their experiments in laboratory mice, using first mouse muscle stem cells and then confirming their results with human muscle stem cells transplanted into mice. They are eager now to learn whether the findings can be scaled up to a degree that might one day be useful in humans with major muscle trauma.