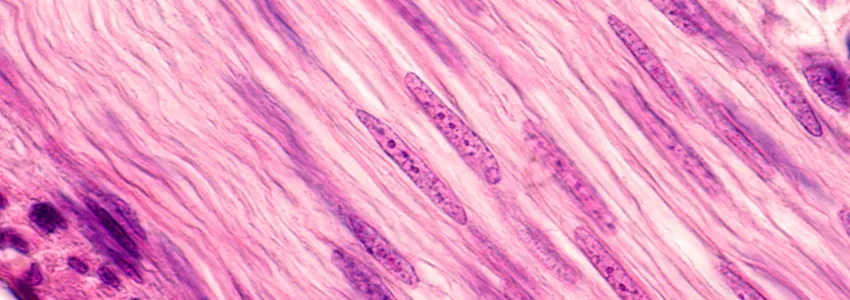

Photo by Jose Luis Calvo, Shutterstock.

Stanford Medicine Scope - September 25th, 2017 - by Krista Conger

Muscle stem cells are wily beasts. As I've written about before, they nestle along our muscle fibers and quietly await the biological red flag that will tell them to leap into action and form new muscle fibers. But exactly how they are activated remains a mystery -- one that doctors and researchers would love to solve as they search for new ways to help patients recover from trauma or surgery, or even to combat normal aging.

Now Brian Feldman, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of pediatrics, and postdoctoral scholar Hongqing Du, PhD, have identified another important player in the muscle regeneration dance. The molecule, Adamts1, has been implicated in fat metabolism and obesity; now it's been shown to also prod muscle stem cells into action via an important signaling pathway called Notch. They published their results in Nature Communications. Importantly, Adamts1 is secreted by immune cells called macrophages that flock to sites of muscle damage.

As Feldman explained to me in an email:

While, in retrospect, it might make intuitive sense that the same cells that are sent into a site of injury to clean up the mess also carry the tools and signals needed to rebuild what was destroyed, it was not at all obvious how, or if, these two processes were biologically coupled. Our data show a direct link in which the clean-up crew releases a signal to launch the rebuild. This was a surprise.

An implicit feature of this set-up is that a cell type that is not part of the muscle lineage and, indeed, is usually only present in low numbers in uninjured muscle, ascends to make a powerful contribution to muscle physiology. To my knowledge, this is the first signal to be defined and traced to a macrophage that is competent to promote the activation of muscle stem cells.

Feldman and Du showed that the macrophages release Adamts1 into the extracellular soup. Once released, Adamts1 nips a bit off a protein on the surface of the muscle stem cells called Notch1 that normally keeps them resting quietly. With Notch1 deactivated, the muscle cells get to work making new muscle fibers.

The researchers confirmed their findings by creating a strain of mice that constantly overexpresses Adamts1 in their muscle tissue. These mice have more muscle mass than their peers when they are young, and they recover more quickly from muscle damage. However, more is not always better. These mice also seem to deplete their supply of muscle stem cells over time, and eventually they become less able than normal mice to repair muscle damage.

The team is optimistic about the results. Feldman explained:

We are excited to learn that a single purified protein, that functions outside the cell, is sufficient to signal to muscle stem cells and stimulate them to differentiate into muscle. The simplicity of that type of signal in general and the extracellular nature of the mechanism in particular, make the pathway highly tractable to manipulation to support efforts to develop therapies that improve health.