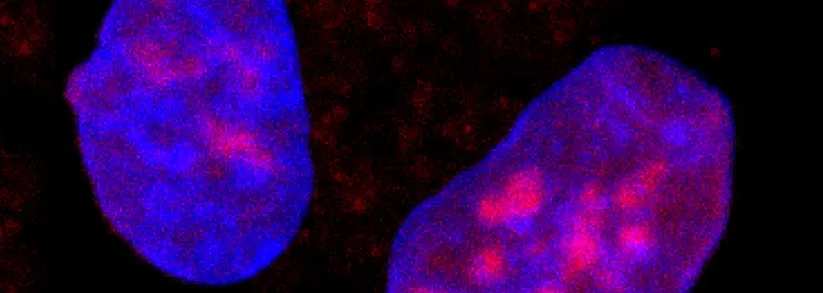

Photo courtesy Howard Chang: Magnified image of cells, visualized with a Stanford invention called ATAC-seq.

Stanford Medicine Scope - May 11th, 2017 - by Michael Claeys

“Cancer is a disease of genes,” says dermatology professor Howard Chang, MD, PhD. So for healthy cells to turn malignant something must go wrong with their genes, right? Not necessarily.

Cancer is often caused by permanent alterations or damage to cells’ DNA — commonly referred to as genetic mutations — but mutations aren’t the entire story. There’s another major component to genetic regulation called epigenetics. Broadly stated, that’s a collection of processes that control or modify gene behavior without damaging the genes themselves. For example, chemical interactions can change which genes are turned “on” in a cell and thereby change its activity, or even what type of cell it becomes.

“All the cells in the body have the same genes, but of course your eye is not the same as your liver,” Chang said. “Cells choose to turn on some sets of genes and not other sets.”

Chang is a leader in the area of cancer epigenetics who has co-authored many publications and developed tools that aid other researchers. For example, Chang is the co-creator of a next-generation test for scanning DNA to assess which of its genes are activated. Called “ATAC-seq” (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with high throughput sequencing), the technique represents an astonishing technological leap; it is one million times more sensitive, 100 times faster and it needs only 1,000th the sample size of the previous DNA scanning assay.

Chang describes the technique as essentially “spray-painting” chromosomes with an engineered enzyme that adheres only to active genes. ATAC-seq enables researchers to map a cell’s genetic activity and try to decipher which genes control which characteristics or activities. In cancer, ATAC-seq is also used to identify potential targets for drugs and other therapies.

Learn more about ATAC-seq and some of the epigenetic research that Chang and his colleagues are conducting at Stanford in the Spring 2017 edition of SCI News, the community newsletter of the Stanford Cancer Institute.