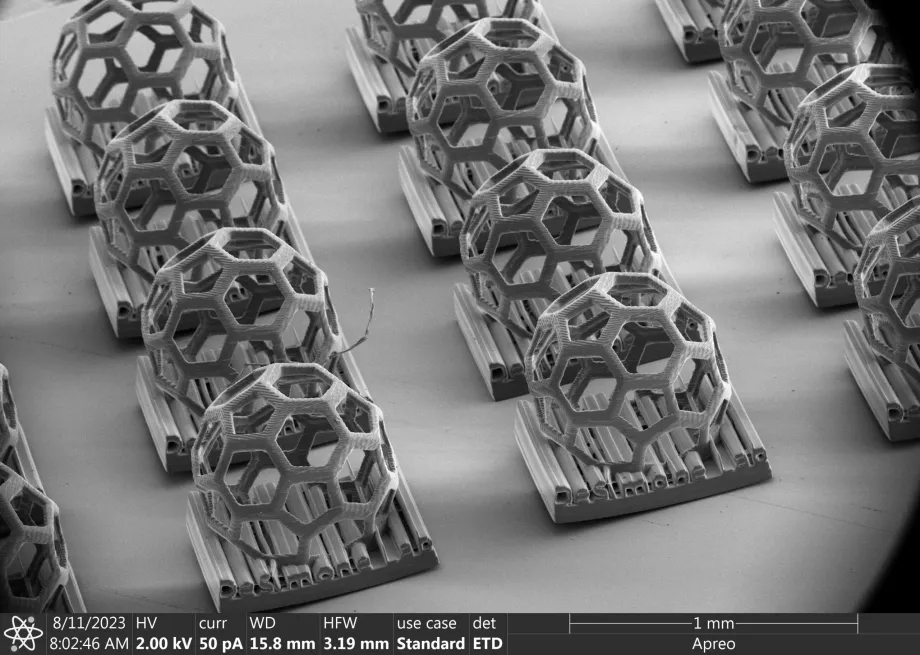

Image credit: DeSimone Research Group, SEM courtesy of Stanford Nano Shared Facilities. The 3D-printed DeSimone lab logo, featuring a buckyball geometry, demonstrates the r2rCLIP system’s ability to produce complex, non-moldable shapes with micron-scale features.

Stanford News - March 13th, 2024 - by Taylor Kubota

3D-printed microscopic particles, so small that to the naked eye they look like dust, have applications in drug and vaccine delivery, microelectronics, microfluidics, and abrasives for intricate manufacturing. However, the need for precise coordination between light delivery, stage movement, and resin properties makes scalable fabrication of such custom microscale particles challenging. Now, researchers at Stanford University have introduced a more efficient processing technique that can print up to 1 million highly detailed and customizable microscale particles a day.

“We can now create much more complex shapes down to the microscopic scale, at speeds that have not been shown for particle fabrication previously, and out of a wide range of materials,” said Jason Kronenfeld, PhD candidate in the DeSimone lab at Stanford and lead author of the paper that details this process, published today in Nature.

This work builds on a printing technique known as continuous liquid interface production, or CLIP, introduced in 2015 by DeSimone and coworkers. CLIP uses UV light, projected in slices, to cure resin rapidly into the desired shape. The technique relies on an oxygen-permeable window above the UV light projector. This creates a “dead zone” that prevents liquid resin from curing and sticking to the window. As a result, delicate features can be cured without ripping each layer from a window, leading to faster particle printing.

“Using light to fabricate objects without molds opens up a whole new horizon in the particle world,” said Joseph DeSimone, the Sanjiv Sam Gambhir Professor in Translational Medicine at Stanford Medicine and corresponding author of the paper. “And we think doing it in a scalable manner leads to opportunities for using these particles to drive the industries of the future. We’re excited about where this can lead and where others can use these ideas to advance their own aspirations.”

Roll to roll

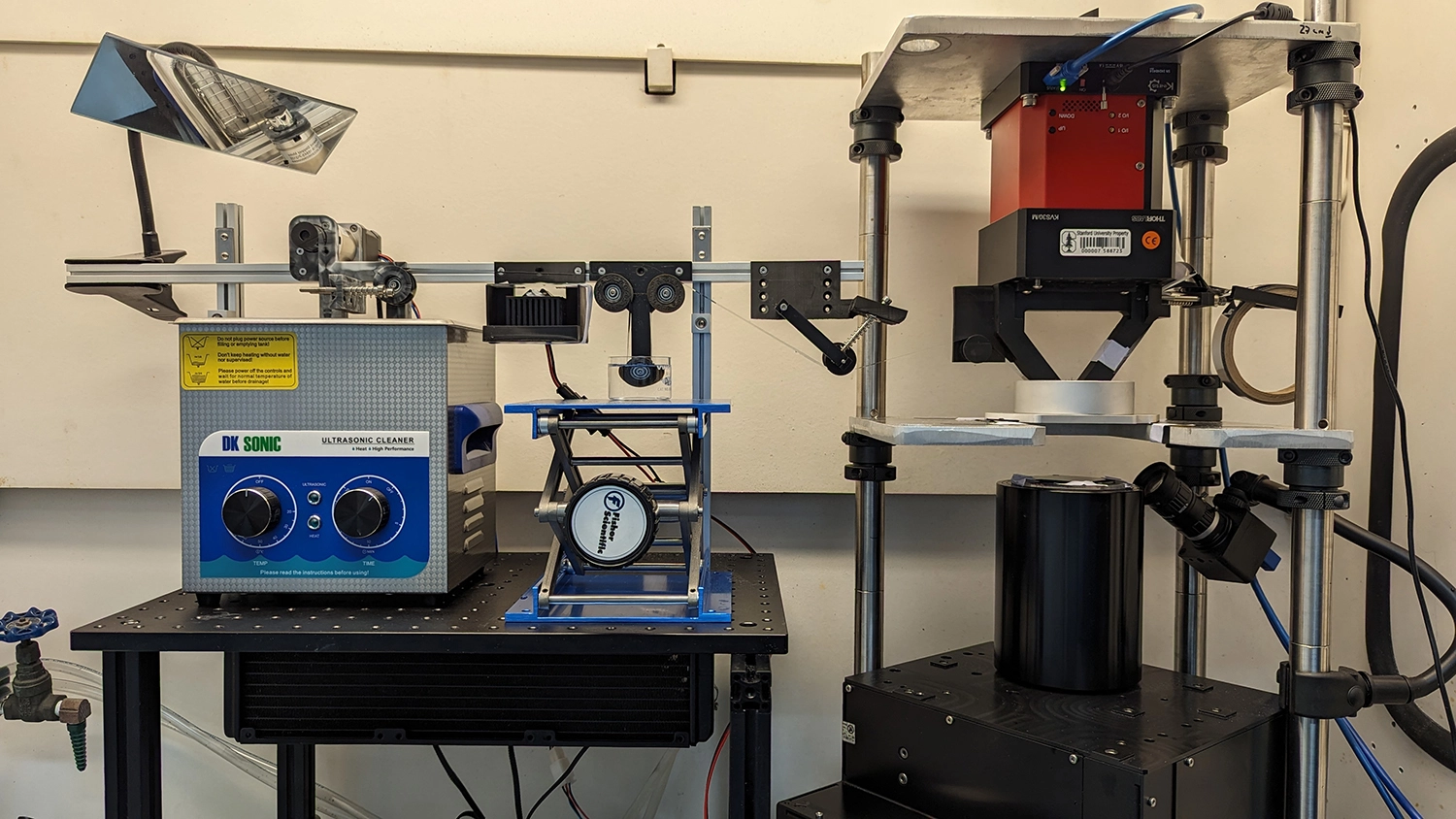

The process that these researchers invented for mass producing uniquely shaped particles that are smaller than the width of a human hair is reminiscent of an assembly line. It starts with a film that is carefully tensioned and then sent to the CLIP printer. At the printer, hundreds of shapes are printed at once onto the film and then the assembly line moves along to wash, cure, and remove the shapes – steps that can all be customized based on the shape and material involved. At the end, the empty film is rolled back up, giving the whole process the name roll-to-roll CLIP, or r2rCLIP. Prior to r2rCLIP, a batch of printed particles would need to be manually processed, a slow and labor-intensive process. The automation of r2rCLIP now enables unprecedented fabrication rates of up to 1 million particles per day.

Image credit: DeSimone Research Group. The r2rCLIP setup in the DeSimone lab runs from right to left. The printing occurs at the area below the red piece.

If this sounds like a familiar form for manufacturing, that’s intentional.

“You don’t buy stuff you can’t make,” said DeSimone, who is also professor of chemical engineering in the School of Engineering. “The tools that most researchers use are tools for making prototypes and test beds, and to prove important points. My lab does translational manufacturing science – we develop tools that enable scale. This is one of the great examples of what that focus has meant for us.”

Interdisciplinary team science The researchers emphasized that this work and where it will go from here reflects and gains strength from the interdisciplinary nature of their team. “This is an integration of disciplinary diversity of hardware, software, materials science, and chemical engineering all coming together,” said DeSimone. “Jason, for example, is a chemist. But if you don’t squint too hard, he sounds like a mechanical engineer. I think he epitomizes a new generation of students in team science.”

There are tradeoffs in 3D printing of resolution versus speed. For instance, other 3D printing processes can print much smaller – on the nanometer scale – but are slower. And, of course, macroscopic 3D printing has already gained a foothold (literally) in mass manufacturing, in the form of shoes, household goods, machine parts, football helmets, dentures, hearing aids, and more. This work addresses opportunities in between those worlds.

“We’re navigating a precise balance between speed and resolution,” said Kronenfeld. “Our approach is distinctively capable of producing high-resolution outputs while preserving the fabrication pace required to meet the particle production volumes that experts consider essential for various applications. Techniques with potential for translational impact must be feasibly adaptable from the research lab scale to that of industrial production.”

Hard and soft

The researchers hope that the r2rCLIP process sees wide adoption by other researchers and industry. Beyond that, DeSimone believes that 3D printing as a field is quickly evolving past questions about the process and toward ambitions about the possibilities.

“r2rCLIP is a foundational technology,” said DeSimone. “But I do believe that we’re now entering a world focused on 3D products themselves more so than the process. These processes are becoming clearly valuable and useful. And now the question is: What are the high-value applications?”

For their part, the researchers have already experimented with producing both hard and soft particles, made of ceramics and of hydrogels. The first could see applications in microelectronics manufacturing and the latter in drug delivery in the body.

“There’s a wide array of applications, and we’re just beginning to explore them,” said Maria Dulay, senior research scientist in the DeSimone lab and co-author of the paper. “It’s quite extraordinary, where we’re at with this technique.”

Additional co-authors are Lukas Rother, who was a visiting master’s student at the time of this work, and Max Saccone, a postdoctoral scholar in chemical engineering and radiology. DeSimone is also a professor, by courtesy, in chemistry in the School of Humanities and Sciences, materials science and engineering in the School of Engineering, and operations, information, and technology in the Graduate School of Business. He is a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance, and the Stanford Cancer Institute, and a faculty fellow of Sarafan ChEM-H, co-director of the Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection, and founding faculty director of the Center for STEMM Mentorship at Stanford.

This research was funded in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program. Part of this work was performed at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities, supported by the National Science Foundation.