Carlos A. Aldrete (left) and Luis Santiago Mille-Fragoso in the lab.

Stanford Engineering News - March 28th, 2025 - by Ula Chrobak

Cell therapies – based on engineering living cells, usually immune cells – have shown promise for cancer therapy, muscle regeneration, and rheumatoid arthritis. But many of these treatments face pitfalls due to the difficulty of controlling engineered cells once they’ve been injected into a patient.

“We don’t have much control of them after we deliver them into the body,” said Stanford chemical engineering PhD student Carlos Aldrete, a co-lead author of a recent Nature Chemical Biology paper debuting a protein-based system that might help solve this problem.

Previous research has proposed DNA-based systems for controlling cell therapies. But inserting DNA into a patient poses risks such as the possibility of introducing cancer-causing mutations. So, researchers in the Gao Lab are engineering protein and RNA systems capable of fine-tuning cell functions in the body, then harmlessly degrading over time. In other words, they have the potential to deliver safer and temporary treatments.

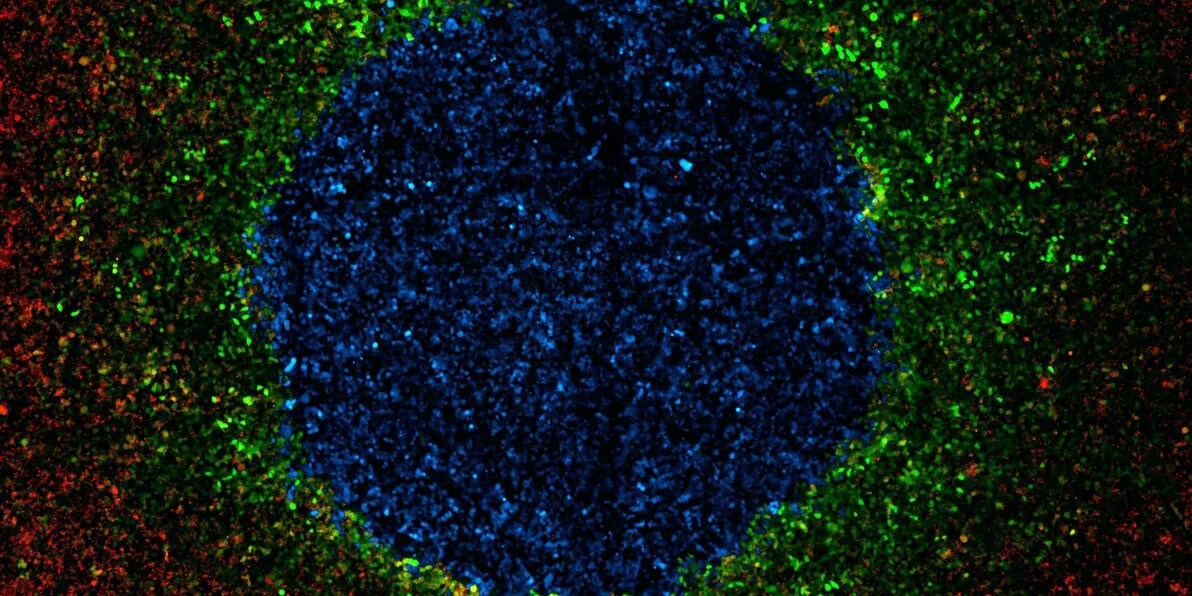

LIDAR is used to sense a secreted molecule (CCL20) and produce a fluorescent protein (Green Fluorescent Protein – GFP). Each dot in this picture is a single cell. CCL20-producing cells are labeled with blue (BFP) and LIDAR-containing cells are labeled in red (RFP). This is a proof of concept for LIDAR-enabled cell-cell communication. | Courtesy of Santiago Fragoso (click to enlarge)

In two recent Nature Chemical Biology papers, the researchers demonstrated how these new tools could precisely control cells, showing promise for their use in cancer therapies and other treatments. “With all the tools we build in the lab, we can make cell therapies more effective and safer at the same time,” said Xiaojing Gao, assistant professor of chemical engineering and senior author on both papers.

An RNA-based sensor to modulate cell outputs

RNA-compatible receptors are one promising route for controlling cells. Cellular receptors are proteins in the cell membrane that transmit an environmental signal inside the cell, which then sets in motion biological functions. In a paper published on March 28, 2025 the team tested the first customizable synthetic receptor constructed from an RNA molecule.

“If we build synthetic receptors, we can make those receptor proteins on the cell membrane sense a specific input and output the desired function,” said Xiaowei Zhang, a PhD student in bioengineering and co-lead author of the paper.

The system – known as ligand-induced dimerization activating RNA editing, or LIDAR – is essentially a modular factory in the membrane of a target cell. The factory contains three parts: two proteins and an RNA sequence. In the absence of a specific signal molecule, the RNA remains dormant. When the signal molecule appears, it glues the two proteins together, which then cues an enzyme called ADAR to edit away a stop sequence in the RNA. The RNA then produces a customized output.

The researchers tested the synthetic receptor by introducing RNA into several cell lines. The team found that LIDAR could output a few types of proteins, including Caspase-9, a cell-killing protein of potential interest in cancer treatment, and a transcription factor that binds to a specific DNA sequence and increases production of an encoded protein.

In short, they demonstrated that the synthetic receptor is modular both in terms of input, the signal molecule activating the system, and output, what it produces. Using the synthetic receptor, “you can virtually produce any protein that can be encoded as a gene,” said Santiago Mille Fragoso, a PhD student in bioengineering and co-lead author of the paper.

In the future, LIDAR could be used in medicine to tamp down on off-target effects of a treatment. This extra layer of control could refine CAR T immune cell cancer treatment, for example, by adding another signal for engineered cells to recognize before attacking tumors, thus preventing unintended effects to healthy cells.

Controlling human cells, with human proteins

Some cancers modify their surroundings in a way that suppresses immune cells – even engineered ones, like those used in CAR T cell therapy. In the Nature Chemical Biology paper published January 15, Aldrete and his co-authors showed that a human protein-based system – humanized drug-induced regulation of engineered cytokines (hDIRECT) – could act like a control knob for immune cells, making it possible to adjust their activity, potentially overcoming cancer’s suppressing effects.

The platform centers around cytokines, which are small but powerful immune-signaling proteins. They are so powerful, in fact, that simply administering them alone would lead to toxic effects because they interact with many different cells.

For that reason, the other two players in the protein circuit control the cytokines. Proteases, known as molecular scissors, can cut the cytokines at specific sites to activate or inactivate them. A small molecule in pill form in turn regulates the protease, controlling the whole process.

To build such a circuit, the team picked the human protease renin, which normally helps regulate blood pressure. Renin is a good candidate because there is already an FDA-approved drug that inhibits it, aliskiren. Because human proteases tend to be “promiscuous,” cutting into a variety of proteins, Aldrete engineered the renin to function only within a certain type of cell.

The researchers next added a “caging domain” to some of the cytokines, which is “literally putting a big bubble around your cytokine,” said chemical engineering PhD student Connor Call, a co-lead author of the paper and co-author of the LIDAR paper. The protease can chop away this cage when increased cytokine activity is desired.

The researchers used messenger RNA to insert hDIRECT into a few cell lines. Without aliskiren present, the engineered renin cut open the cages and set the cytokines loose, which then signaled for the T cells to proliferate. Adding aliskiren inhibited renin, sending the cytokines back to their cages and dampening their signals to the T cells. Both directions are needed – T cells that are too activated for too long can exhaust and stop working.

If the protein circuits prove effective, future clinicians may be able to toggle the activity of CAR T cells with the drug, instructing the engineered immune cells when to ramp up their attacks on tumors and when to tone them down. “Our work establishes the first control knob based on a human-derived protease and its clinically approved small-molecule inhibitor, clearing a major hurdle for protease control to make an impact in human health,” said Gao, the study’s senior author.

Multiple layers of control in medicine

The two systems represent two angles from which to add a layer of control to cells. In theory, protein-based control knobs like hDIRECT are efficient because they cut down on the step of translating RNA into proteins. But RNA is easier to tailor for specific uses by swapping the base pairs in its sequence. In comparison, proteins have to be precisely engineered so that their structure fits snugly with target molecules. “Every protein has its little quirks,” said Gao. “Usually there’s more engineering effort required.”

It also may be possible to use both modes at once. For instance, researchers could program the LIDAR system to produce the hDIRECT proteins only when a specific environmental signal is present. Then, on top of that, aliskiren adds a further level of control in protease activity. “They can work together because they work on different levels of the central dogma,” said Gao.

The possibilities for RNA and protein-based control knobs are vast. In addition to cancer treatment, a future protein circuit treatment could stimulate the growth of injected stem cells while reducing inflammation, which would accelerate the regrowth of muscles after an injury. And synthetic receptors could be adapted for health diagnostics. One example: A patient receives an RNA shot, which goes to the liver and produces a receptor that outputs a peptide in the presence of cancer markers, which can then be measured in urine samples. “We’re really opening the door up to these different therapies being real,” said Call.

Xiaojing Gao is also a faculty fellow at Sarafan ChEM-H and a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance, the Stanford Cancer Institute, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

Other Stanford co-authors of the hDIRECT paper include bioengineering PhD student Lucas Sant’Anna and chemical engineering postdoctoral scholar Alexander Vlahos. The authors also include researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Other Stanford co-authors of the LIDAR paper include former bioengineering PhD student Eerik Kaseniit, postbaccalaureate scholar Arden Lee, chemical engineering postdoctoral scholar Meng Zhang, biology PhD student Yixin Hu, and former undergraduate researcher Yunxin Xie.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Longevity Impetus Grants, the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance Agility Project Grant, Stanford Bio-X Interdisciplinary Initiatives Seed Grant Program, the Stanford Graduate Fellowship, the Stanford Cancer Institute Innovation Award, the Bio-X Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship, the Sarafan ChEM-H CBI training program, the Sarafan ChEM-H/IMA Postbaccalaureate Program in Target Discovery, the National Science Foundation, and the International Human Frontier Science Program Organization.

originally published at Stanford Engineering News