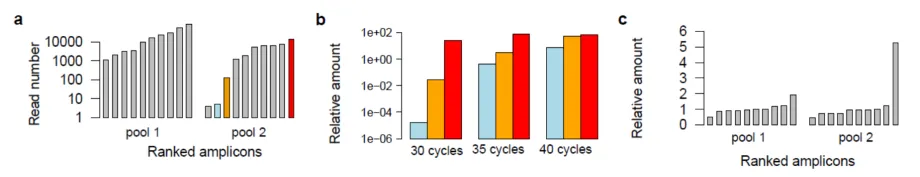

The relationship between PCR cycle number and the uniformity of the multiplex PCR products - from publication in Nature Methods.

Inside Stanford Medicine, May 19th, 2014, by Krista Conger

It's abundantly clear by now that the sequence of our genes can be important to our health.

Mutations in some key areas can lead to the development of diseases such as cancer.

However, gene sequence isn't everything. It's necessary to know when and at what levels that mutated gene is expressed in the body's cells and tissues.

This analysis is complicated by the fact that most of us have two copies of every gene — one from our father and one from our mother — with the exception of sex chromosomes X and Y. (People with conditions caused by an abnormal number of chromosomal copies, such as Down syndrome, are another exception.)

These two versions of the same gene (individually called alleles) are not always expressed in the same way (a phenomenon called allele-specific expression). In particular, structural changes or other modifications to the alleles, or the RNA that is made from them, can significantly affect levels of expression. This matters when one copy has a mutation that could cause a disease like cancer. That mutation could be very important if that allele is preferentially expressed, or less important if its partner is favored.

Understanding relative levels of allele expression is therefore critical to determining the effect of particular mutations in our genome. But it's been difficult to accomplish, in part because allele-specific expression can vary among our body's tissues.

Stephen Montgomery, PhD, assistant professor of pathology and of genetics, and Jin Billy Li, PhD, assistant professor of genetics, have devised a way to use microfluidic and deep-sequencing technology to measure the relative levels of expression of each allele in various tissues. They described the technique in the January issue of Nature Methods.

Now they've taken the research one step further to look at the varying expression of disease-associated alleles across 10 tissues from a single individual.

"We were able to learn that as many as one-third of personal genome variants (that is, potentially damaging mutations that would be detected by genome sequencing within an individual) can be modified by allele-specific expression in ways that could influence individual outcomes," Montgomery said. "Therefore, just knowing a variant exists is only one step toward predicting clinical outcome in an individual. It is also necessary to know the context of that variant. Is the damaging allele in a gene that is abundantly expressed within and across an individual's tissues?"

Montgomery and Li published these most recent findings May 1 in PLOS Genetics. Together, their work has been awarded a grant from the National Human Genome Research Institute to study allele-specific expression in thousands of tissues from 100 donors during the next three years. The grant is part of the institute's Genotype-Tissue Expression effort.