Photo by bikeriderlondon, Shutterstock.

Stanford Engineering - April 22nd, 2016 - by Carrie Kirby

Walking to a morning meeting, chemical engineering Professor Zhenan Bao picks up the pace, slightly elevating her breathing and causing her heart rate to rise. But these physiological changes go unrecorded because Bao has left her personal activity tracker at home, in part because it doesn’t provide enough detail about what really matters to her. “They’re not providing sufficiently accurate information that people care about,” she says.

Bao is on quest to develop what she calls “the interface between human and machine” – electronics that will initially be used externally to help everyone from the fitness buff tracking heart rate to the medical patients managing diabetes. Less obtrusive than today’s rigid wristband devices, these flexible, biocompatible electronics would be like a second skin – a technological way station on the path toward creating a sophisticated artificial skin for people with prosthetic limbs.

Bao has dedicated much of her career to developing these kinds of flexible electronics. Previously, as a researcher at Bell Labs, she developed the first plastic transistor to be produced entirely by a printer and worked on the first flexible electronic paper. She left Bell for Stanford in 2004 to look beyond the industrial applications for flexible electronics, such as computer displays and sensors for automobiles and robotics. She saw the greater challenge and most significant potential in developing a new generation of flexible, stretchable electronics – an artificial skin – that will one day communicate directly with the human brain just like our natural covering. “I feel that this is an area that, if we are successful, will really benefit people,” she says.

The ultimate application of Bao’s vision would be covering a prosthetic limb with a sheet of electronic sensors that act like human skin and allow an amputee to “feel” everything from a child’s kiss to a hot pot handle.

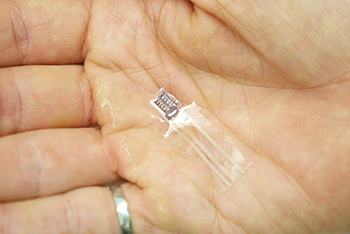

Image courtesy of Bao research group: The pressure sensors on

this flexible plastic strip approximate some aspects of touch. This

technology could lead to artificial skin to restore some sensation

to people with prosthetic limbs.

To achieve this, the material would need the physical characteristics of skin, sensors that mimic the many different types of nerves in skin, flexible circuitry to carry electronic signals from the sensors, and a technology to translate this electronic sensory information into the equivalent of nerve impulses understood by the brain.

All of this is difficult. Today’s electronic materials are rigid. They don’t bend or stretch. And even after creating flexible electronics, the challenge remains of creating an interface between electronic circuits and biological nerves.

“To put a piece of synthetic material onto the body and allow it to actually communicate with the brain requires breakthroughs in many different areas,” Bao says.

Her lab has made a start. Its most advanced material can mimic human skin’s pressure-sensing capability and generate electrical pulses that our brain would understand. Her team is striving to add other sensations and temperature sensitivities, to enable the artificial skin to sense everything that human skin can feel. She is collaborating with neurosurgeons and neuroscientists on how to make the electronic-to-biological connection. Despite the complexity of the project, she is optimistic that an early version of prosthetic skin could be tested in just a few years.

On the way toward that ambitious goal of creating skin-like coverings for prosthetics, Bao believes her smart, flexible electronics could create products more useful than the plastic wristbands in use today.

“Flexible electronics that provide intimate contact with human bodies allow us to potentially extract more accurate information about health conditions,” she explains. “This would provide information that people actually care about – blood pressure, for example, or glucose levels or the chemicals that may be generated in sweat that are related to stress.”

Already her team is developing a prototype bandage-like wearable blood pressure sensor that could comfortably provide continuous monitoring for patients with cardiovascular problems.

In addition to this bandage model, Bao imagines designing flexible electronics into clothing fabric. At the same time she is exploring the use of biocompatible electronics as subdermal implants.

“Think about these as electronics devices that you can wear inside the body,” she says.

At a recent conference for Stanford’s SystemX Alliance, which brings together industrial and academic researchers, Bao described one such concept: a smart, flexible device that could be installed on the heart of a patient suffering from arrhythmia to provide doctors with a record of the irregular current flows that cause the problem.

Another subdermal application would be monitoring a patient’s brain pressure by implanting a wireless pressure sensor between the skull and the brain.

Adding another dimension to this work, her lab recently created a new class of super-elastic polymers that can stretch up to 100 times their original length. These super-stretchy materials can repair themselves if they are punctured or torn. Most importantly, when subject to an electrical charge these materials pulsed or twitched, suggesting their potential to serve as a new type of artificial muscle.

Bao’s team has many other research projects underway stemming from the skin-inspired materials they have developed, including a self-healing conductive material that dramatically improves the performance of lithium-ion batteries – something that could help portable electronics and electric vehicles work longer.

Bao’s broad and varied achievements have earned her recognition as a member of the National Academy of Engineering, among many other professional honors and awards.

But her passion and focus often return to the challenge of replicating human skin.

“I wanted to dream big, to see what kind of science fiction we can make into a reality,” she says. “Artificial skin is something really out there that would allow us to be more creative, more imaginative, and break away from our normal thinking.”