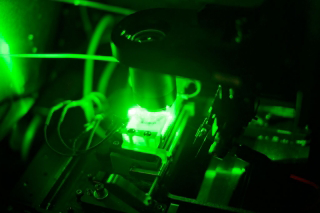

Photo by Charlie Wilkes: Two Eterna players study a screen showing an RNA molecule designed using the Eterna

Medicine computer game. Above is the display output from a custom-built laser microscope for examining the thou-

sands of RNA molecules designed by players. Each green dot represents a different player-generated design.

Stanford Medicine News Center - May 2nd, 2016 - by Jennie Dusheck

Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine are releasing a new version of a web-based video game that will harness the creative brain power of thousands of nonscientist players.

The goal in coming months is for Eterna Medicine players to design a molecule that could help spur the development of a new tuberculosis test.

Tuberculosis infects a third of the world’s population and kills about 1.5 million each year. Yet health organizations lack a simple-to-use blood test that can detect active infection in many patients, especially in remote villages.

Like a previous iteration of the Eterna game, the new version challenges players to build molecules of RNA with increasingly difficult-to-design shapes.

RNA is DNA’s inventive cousin. DNA molecules form the standard two-stranded double helices; their threadlike shape is stable and comparatively stiff. In contrast, RNA is single-stranded, floppy and can spontaneously fold into myriad shapes. Each shape has its own biological properties, many of which can be useful to biomedical researchers.

Eterna’s co-creator Rhiju Das, PhD, said Eterna Medicine could someday allow citizen-scientists to invent their own pharmaceuticals. “It’s going to sound like science fiction,” he said. For now, Das, an associate professor of biochemistry at Stanford, is turning loose 100,000 registered Eterna players to pilot a new route to controlling the tuberculosis pandemic.

Games with real-life consequences

Eterna, the first version of the video game, was launched five years ago as a way to let nonscientists design potentially useful biomolecules that are stable enough to function inside a living cell. Over the years, the players have become more and more expert in designing complex RNA molecules. They are so good at it now that the players recently co-authored an article in the Journal of Molecular Biology describing a set of rules for predicting how difficult it will be to build a given RNA molecule.

Photo of Norbert von der Groeben: Rhiju Das says a game

like Eterna Medicine could someday enable citizen-scient-

ists to invent their own pharmaceuticals.

Now Das has set a new challenge in front of them: design a molecule that could help save the lives of millions of people.

Recently, assistant professor of medicine Purvesh Khatri, PhD, and his team came up with a test that can accurately diagnose TB from a simple blood sample. The test looks at the expression levels of three different genes. Cells “express” genes when the cell transcribes a gene into a length of RNA.

In the Khatri lab’s TB test, when the three genes are expressed in certain proportions, doctors know the patient has TB. But how to calculate those proportions in a simple test on a stick — like a pregnancy test — is the challenge. To do so, Das said, they need a molecule that can calculate the proportions of three molecules. Right now, there’s no single molecule that can make that calculation.

But Das said the Eterna game, powered by the minds of thousands of players, can theoretically create a molecule capable of such a calculation. His hope is to get tens of thousands of designs, of which perhaps a thousand may have potential. Das’ lab will then test all of these molecules to see how well they work in the lab. If successful, a subset of 10 to 20 molecules will be tested to see which work best in a real stick-test.

Said Das, “Eterna Medicine is a little different from the original Eterna because we are trying to recruit people to make something with an eventual real-world impact.”

How can a molecule solve an equation?

When a person is being tested for tuberculosis with the Khatri TB test, RNA molecules circulating in the blood reveal the levels of expression of three genes. If Eterna players succeed, they’ll come up with an Eterna-built RNA molecule, called “OpenTB,” that has three parts. RNA readily binds to other RNA molecules. So, if designed right, each part of OpenTB can bind to one of the TB-related RNA molecules. And when each TB-related RNA from patient blood binds to OpenTB, it will change OpenTB’s shape.

Photo by Charlie Wilkes: A slide carrying an array of RNA

molecules designed by Eterna players is placed under a

special laser microscope designed and built by the Das

and Greenleaf laboratories at the School of Medicine.

The OpenTB molecule will assume different shapes depending on the proportions of the three kinds of TB-related RNA present in the blood sample. “If I have a lot of RNA molecules A and B around,” said Das, “OpenTB will fold into shape 1. But if there’s a lot of C around, OpenTB will fold into shape 2.”

For Das’ plan to work, shape 1 also must be able to bind a fluorescent tag, while shape 2 must not bind the tag. So individual molecules with shape 1 would emit light and those with shape 2 would not.

By measuring the brightness of the light, said Das, you can calculate what proportion of Eterna molecules have folded into shape 1, revealing the proportion of RNAs A and B relative to C. If the light is above a certain threshold of brightness, you know the patient has active tuberculosis.

New paradigm in translational research

Khatri said the idea for using a TB test came about when he and Das were seated together at a conference having dinner. They got to talking, he said, and realized that the TB test might be a perfect challenge for Eterna players. But Das told him that anything more complicated than three or four genes would involve so many possible configurations, it would be almost impossible to solve.

“I love this idea because it changes the biological research paradigm,” Khatri said. “If successful, it would allow us to say, ‘We can use publicly available data — ultimately provided by patients themselves — to find a diagnostic signature of one of the biggest killers of mankind. And then we can engage the public to design molecules that can help deploy that test to help other patients using a video game platform.’”