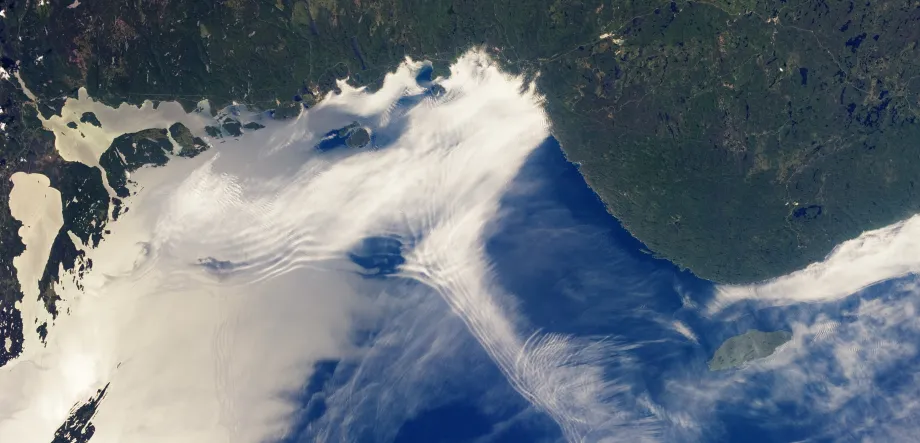

Gravity waves can produce parallel bands of clouds, as seen in this 2013 view of Lake Superior from the International Space Station. | ISS Crew Earth Observations experiment and Image Science & Analysis Laboratory, Johnson Space Center

Stanford Report News - February 4th, 2026 - Ula Chrobak

Global climate models capture many of the processes that shape Earth’s weather and climate. Based on physics, chemistry, fluid motion, and observed data, hundreds of these models agree that more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere leads to hotter global temperatures and more extreme weather.

Still, uncertainty remains around how seasonal weather patterns and atmospheric systems like the jet stream will respond to global warming. Some of this uncertainty stems from the way models approximate the effects of relatively short-lived, small-scale phenomena known as gravity waves.

Unlike gravitational waves, which distort the fabric of space-time, atmospheric gravity waves form around strong convective storms or when a pocket of air hits a mountain or other obstacle. The pocket moves up until it becomes denser than the surrounding air, then sinks back down. Like a pebble dropped into a pond, that sinking air creates a ripple outward.

These ripples help to drive circulation in the atmosphere and influence weather around the world. Through their influence on high-altitude winds called jet streams, they can affect the trajectory of midlatitude storms and even flight times between New York and London. Gravity waves excited at lower latitudes also frequently bump into the polar vortex, strong winds circulating high in the stratosphere near Earth’s polar regions.

Over Antarctica, gravity waves play a key role in breaking up the winter polar vortex as part of the transition to spring. Over the Arctic, disruptions to the polar vortex can bring the kind of extreme winter weather that has recently gripped much of the southeastern and eastern United States.

“We want to represent atmospheric gravity waves as propagating the way that they actually do,” said Aditi Sheshadri, an assistant professor of Earth system science in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and senior author of a new study showing how machine learning algorithms that predict the effects of atmospheric waves can be incorporated into global climate models.

Climate model limits

Climate models currently miss most of the effects of gravity waves. For instance, while the Antarctic polar vortex tends to break down in mid-November, climate model simulations predict its decay in December. This is called the “cold pole bias” because the models overestimate how long winter will last in the Southern Hemisphere.

Climate models don’t fully capture gravity waves because they are often based on a grid of 100-by-100-kilometer square columns. In each column, physics equations describe the movement of air and water. Many gravity waves are too small to register at this resolution, like a ripple in a puddle that a low-resolution photo doesn’t capture. Other gravity waves ripple out over distances long enough to cross 10 or more squares in the grid. But, due to computational constraints, climate models do not capture horizontal gravity wave movement. Recognizing these gaps, Sheshadri and collaborators launched DataWave, an international effort focused on improving observations and modeling of gravity waves.

Machine learning for gravity waves

In some of their latest research, published in the Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, the Stanford team trained machine learning algorithms on three years of estimates of atmospheric conditions, including gravity waves. These estimates were derived from data recorded by various instruments, including satellites, weather balloons, and radar, between 2010 and 2014.

After training the algorithm, the team used this new model to predict gravity waves for 2015 and compared predictions from the model to the actual data for that year. To further refine the gravity wave algorithms, the researchers trained them on a few months of higher-resolution data. As they added more data, they found the predictions of gravity waves grew even more precise.

Essentially, the model played a “fill in the blank” game so the team could test its answers. “It captures pretty much the whole spectrum of gravity waves,” said Aman Gupta, lead author on the two new studies with Sheshadri and a physical science research scientist in Sheshadri’s lab at Stanford.

This is the first example of a machine learning algorithm learning from global data to predict gravity wave effects, said Sheshadri. Because it’s not constrained by grid boxes, it can better predict the ripple effects of the atmospheric waves. The approach also shows a path toward better modeling of other small-scale systems like clouds and ocean eddies.

The team has already connected the machine learning model to a major climate model run by the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Linking the two models took months, because they were developed in different coding languages. But now, the new gravity wave model is working in harmony with the older climate model. “It breaks decades of gridlock because models have traditionally been single-column,” said Sheshadri.

In a related study, also published in Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, Sheshadri and Gupta have developed a second model that could further improve the representation of gravity waves in global climate models. This model repurposed a large AI foundation model built by NASA for weather and climate research, which itself was trained on 40 years of atmospheric data.

The team hopes the research can help improve representations of these processes and overall fidelity of climate models. Climate models today still have significant uncertainties, partly because the underlying equations don’t accurately represent smaller individual atmospheric processes. “We would like to get the answer right, for the right reasons,” said Sheshadri. Ensuring the equations of climate models capture the physics of gravity waves and other forces will make predictions more robust and clean up inconsistencies like the cold pole bias.

Sheshadri is also a member of Stanford Bio-X and a center fellow, by courtesy, with the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. The team also included researchers at the University of Alabama, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, NASA, IBM Research, and Development Seed.

The research received funding from Schmidt Sciences, the National Science Foundation, and NASA.