Image by Kateryna Kon, Shutterstock.

Stanford Medicine Scope - November 29th, 2016 - by Ruthann Richter

Consider the lowly worm. For some, it’s just a garden pest. But for more than a billion people in the developing world, parasitic worms can be a pernicious threat, causing disease, disability and sometimes death.

In a newly published perspective, Stanford researchers and a host of distinguished colleagues urge the World Health Organization to develop sweeping new guidelines to help end parasitic worm diseases, one of the world’s most prevalent health problems. They call for greatly expanded treatment for these diseases, which could save years of human suffering and an estimated $3 billion in lost productivity — similar to the impact of the Ebola and Zika epidemics of recent years, they say.

“Now everyone is coming together to say, ‘Now is the time, after more than a decade of new experience and data, to update the way we do things,’ Nathan Lo, a Stanford MD/PhD candidate who is the first author, told me. “There is so much opportunity, whether it’s expanding treatment from children to the entire community or bringing in other strategies, such as sanitation, to strengthen the way we approach these diseases.”

Lo’s 17 co-authors include the founders of the field of neglected tropical diseases, as well as leading scientists from the U.S. Agency for International Development, pharmaceutical companies and nonprofits that support treatment programs. Many of them were involved in developing the original strategy for treating parasitic worms in 2001 and now call for change.

The perspective is published today in Lancet Infectious Diseases and coincides with a WHO meeting in Geneva where officials, including many of the authors, are gathering to consider new treatment guidelines.

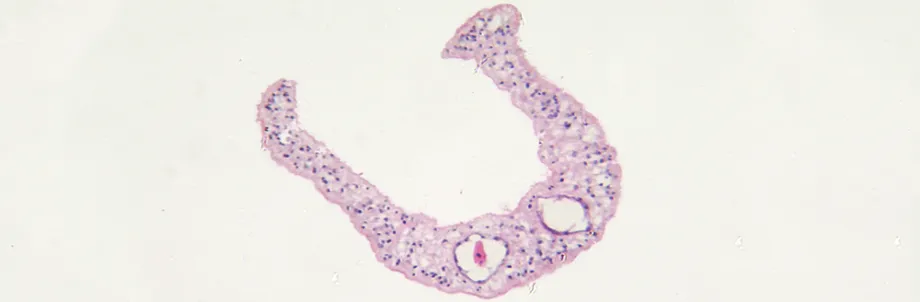

The worms they are targeting include the Schistosoma parasites and the soil-transmitted helminths, such as hookworm and roundworm, which together afflict an estimated 1.5 billion people in some 112 countries. The Schistosoma worms reproduce in fresh water snails and may infect those who bathe in contaminated rivers and lakes. The soil-transmitted helminths are mainly found in soil, and once they find their way into the body, they produce eggs that can be transmitted to others through skin penetration or ingestion of human feces in soil or water supplies. These parasites can cause symptoms ranging from anemia, malnutrition and growth stunting to infertility, bowel obstruction and fatal liver, bladder and intestinal disease. About 20,000 people die of complications from these parasitic infections every year.

“The World Health Organization has been leading the charge against these infections through its guidance around control strategies,” said Jason Andrews, MD, assistant professor of medicine and senior author of the perspective. “The evidence has evolved over the past decade but the guidelines have not kept up. We found that engaging many of the leading scientists, donors and implementers that there was broad consensus about the need to update the global strategy for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth control and elimination.”

Current WHO policies, which date back to 2001, call for treating only pre-school or school-aged youngsters with very low-cost medications that effectively knock down the worms. But often the treated children become reinfected by adults or others in their communities.

The scientists argue for expanding drug treatment to entire communities that are at risk, a strategy that has been shown to be highly cost-effective. These mass treatment programs should be combined with other initiatives to improve water quality, sanitation and hygiene practices, as well as programs to control the proliferation of water-borne snails that harbor the worms, they say. The strategies may vary from country to country, depending on needs and resources, and guidance should be given accordingly, Andrews said.

“We have proposed more specific guidance for countries that are seeking to reduce morbidity, versus those that are approaching elimination, as we believe that different strategies are required for different scenarios,” he said.