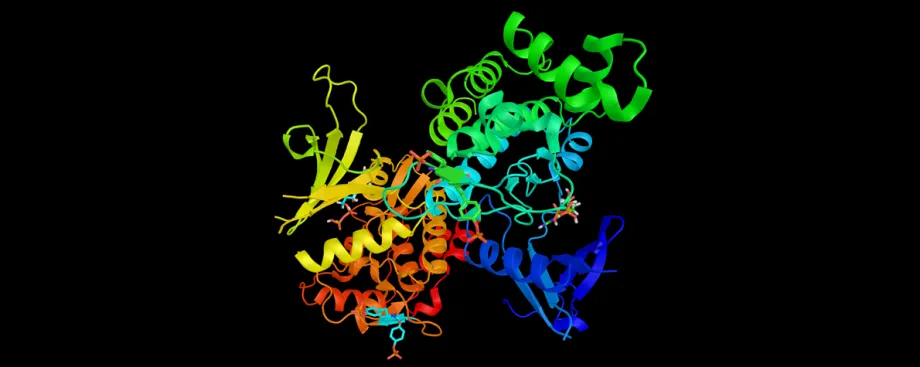

Graphic by ibreakstock, Shutterstock: A rendition of a Janus kinase protein. Stanford scientists have discovered the structure of one of these proteins, which play a role in some cancers and autoimmune diseases.

Stanford Medicine News Center - March 10th, 2022 - by Christopher Vaughan

For more than 25 years, researchers around the world have been trying to find the structure of Janus kinases, or JAKs, a class of proteins that play a key role in cellular signaling and that have been tied to many cancers and autoimmune diseases. Now, Stanford School of Medicine researchers have learned the architecture of one of these proteins, providing a blueprint for understanding JAKs. The knowledge could help scientists elucidate a fundamental mechanism in biology, allowing them to better understand and treat these diseases.

Dr. K. Christopher Garcia.

“There has been quite a horse race to solve this problem,” said Christopher Garcia, PhD, professor of structural biology and of molecular and cellular physiology. “I’ve been at this since I was a postdoc, so it’s extremely gratifying to get an answer.”

“The result not only resolves a fundamental question of cell receptor signaling, but also provides the first look at how a specific mutation in these JAK proteins causes blood cancers,” Garcia added.

The results were published online March 10 in Science. Garcia, the Younger Family Professor, is the senior author. Graduate student Caleb Glassman and postdoctoral scholar Naotaka Tsutsumi, PhD, are co-lead authors.

A first step toward cancer treatment

“Understanding the structure of Janus kinases addresses a huge unmet need in cancer therapy development,” said Ravi Majeti, MD, PhD, professor of hematology and the RZ Cao Professor, who was not involved in the research. Majeti said that JAK mutations are common among myeloproliferative neoplasms, or MPNs, a family of chronic disorders characterized by abnormal blood cell production. “We have a great need for new treatments for MPNs, which can evolve into deadly, acute leukemias,” he said.

Caleb Glassman.

The JAK protein that Garcia and his colleagues imaged has a type of mutation, called a VF mutation, that is associated with a number of MPNs. Genetic mutations can alter the structure of the protein, changing its interaction with cytokine receptors.

Cytokines are cell-signaling molecules, often compared to hormones in terms of the breadth and power of their effects. Interleukins, for instance, which fight invading viruses, are cytokines. Cytokines work by locking onto a cytokine receptor on the surface of cells.

“The cytokine forms a bridge between the receptors and the JAK proteins inside the cell,” Garcia said. This coupling of molecules is then able to effect other chemical changes in the interior of the cell, altering the cell’s behavior.

“The VF mutation is a single amino acid change in this very large protein, made up of over 1,000 amino acids,” Garcia said. “But what we found is that this single amino acid change acts like a dab of glue, so that the JAK proteins and the cytokine receptor bind together and create a positive signal inside the cell even in the absence of a cytokine molecule.”

When the VF mutation produces this molecular glue, “It’s like a light switch that is always on, and the signaling can lead to the uncontrolled cell growth that characterizes cancer,” Garcia said.

‘Revolutionary advances’

Garcia and other researchers have for years used a wide variety of techniques to find the structure of JAK proteins. But key to cracking the problem, Garcia said, were the imaging advances of the past decade.

“Traditional X-ray crystallography was unable to show the structure of JAK given its large size and flexibility. But in the past 10 years, technical improvements in cryo-electron microscopy have allowed us to create fairly high-resolution images of large and complex molecules,” Garcia said. “The Stanford and HHMI Cryo-Electron Microscopy facilities were key to getting this result.”

Now that they have a blueprint for the family of JAK proteins, Garcia said, “We’ll be able to use it to look at the structures of various JAK mutations and design molecules to treat disease caused by specific mutations.”

Garcia is a member of the Stanford Ludwig Center for Cancer Stem Cell Research and Medicine and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

Other Stanford researchers who contributed to the study were postdoctoral scholar Robert Saxton, PhD, and research specialist Kevin Jude, PhD.

The research was supported by the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Institutes of Health (grant R37AI51321), the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation, a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and a Human Science Frontier Program Organization Fellowship.