Stanford Report - January 28th, 2009 - by Chelsea Anne Young

Scientists from Stanford and IBM have improved the sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging by 100 million times using a new technique for measuring tiny magnetic forces. The sensitivity improvement allowed a dramatic improvement of resolving power, achieving a resolution down to 4 nanometers (nm).

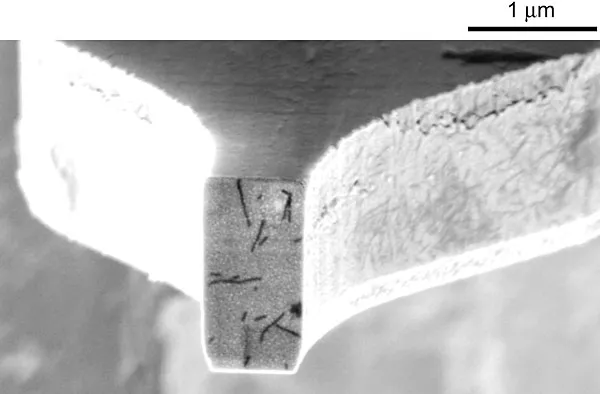

In a recent paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers released pictures taken with the new MRI technology of tobacco mosaic virus particles that span only 18 nm in width. For a little perspective, 80,000 nm is approximately the diameter of a human hair.

"We would like to improve the technique so that we can eventually determine the atomic structures of proteins," said Dan Rugar, a consulting professor at Stanford and the lead IBM researcher on the project. "To understand how these proteins function as little nanomachines in your body, you have to understand the structure."

"Armed with this new structural information, biologists would have unprecedented insight into how and why proteins perform their biological function," said Martino Poggio, which could improve understanding of the chemical world and broaden the potential for targeted drug design.

"Armed with this new structural information, biologists would have unprecedented insight into how and why proteins perform their biological function," said former Stanford postdoctoral scientist Martino Poggio, a co-author on the PNAS paper.

Such knowledge would improve understanding of the chemical world and broaden the potential for targeted drug design, according to the two researchers.

The research was partially funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation, awarded to the Stanford Center for Probing the Nanoscale (CPN) four years ago. The scientific breakthrough resulted from many years of collaboration between IBM's Almaden Research Center and Stanford. Both Rugar and Poggio are CPN members.

"I think that we couldn't have done it so successfully without this partnership between Stanford and IBM," said CPN's deputy director, physics Associate Professor David Goldhaber-Gordon, who co-founded the program five years ago with the mission of developing new tools for measuring and imaging properties on the nanoscale.

Frequently employed by doctors to look below the surface of the skin, traditional MRI takes advantage of the magnetic signals generated by spinning protons within the nuclei of hydrogen atoms contained in water and organic materials inside the body. The directions of the spins of the protons are aligned using a powerful magnetic field. Then, radiofrequency fields are applied to alter this alignment. A detector measures the resulting changes in the overall magnetic field. A computer transforms this information into a three-dimensional map of hydrogen density that distinguishes different types of tissue. This technology can reveal a tumor among healthy tissue, for example.

"But MRI is traditionally quite insensitive," said Rugar. "It's very hard to scale normal MRI down to a small scale."

The barrier to increased sensitivity lies in the way the machine detects magnetic signals. "In an MRI machine the signals are detected by putting a [looped] coil near the person's body," explained Rugar.

When the magnetic field changes due to changes in the alignment of the spinning protons, "it induces a voltage in the loop," said Rugar. "The machines measure a little voltage on a coil. It turns out that it's hard to make that super-sensitive."

Since the mid-nineties, Rugar has been researching ways to improve the resolving ability of MRI technology. The recently published PNAS paper unveiled "a much more sensitive way to detect MRI signals and to extend it from the macroscale, the millimeter scale, down to the nanometer scale," he said.

This new technology, called magnetic resonance force microscopy (MRFM), relies on manipulating hydrogen nuclei just like traditional MRI. However, Rugar and his team of Stanford and IBM researchers devised a much more sensitive method of detection, thereby improving the resolving power to 4 nm.

The theory behind the detection method of MRFM is "one that you're familiar with from elementary school," Rugar said. "That is, if you take two magnets and you put them close together they're either going to attract or they're going to repel. We actually measure that force."

To measure such minute forces, Rugar and his team invented a completely novel setup. The virus particles used as samples sit on an extremely flexible microscopic cantilever, which Rugar describes as a "little silicone diving board."

Then, using an oscillating magnetic field, researchers "flip the direction of the nuclear spin."

Bringing another tiny magnet close to the spinning particles will produce either an attractive or repulsive force that is measured by vibrations in the cantilever.

By measuring forces generated as the tiny magnet is positioned at 8,000 different points around the sample, scientists can generate a three-dimensional map of hydrogen density, thereby creating a three-dimensional image.

In addition to being vastly more sensitive than traditional MRI technology, MRFM also has several advantages over existing imaging technology, such as X-ray crystallography—which is only effective for a small percentage of proteins—and electron microscopy, which employs high-energy electrons that can damage the sample.

Additionally, MRFM is chemically selective, meaning that it can be used to look at a variety of elements to obtain a more detailed picture of the sample's structure. "For example, if you wanted to see where the DNA is, you can tune in to phosphorous," said Rugar.

"This information adds to the structural information to provide a more complete picture of a sample," said Poggio.

Each scan takes several days and must be conducted in a super-cooled vacuum, said Rugar.

The technology is still in the development stage and the researchers do not yet have plans for commercialization, he added.

As for the future of MFRM technology, both researchers have high hopes. "I envision a machine, similar to the one we have today, in which we load a new protein or molecule, whose structure we don't know, every month or so," said Poggio. "In that time we make a detailed atomic-scale image of the protein or molecule.

"If we are able to obtain 10 to 100 times finer resolution, MRFM would truly represent a breakthrough for structural biologists."

he relationship between Stanford and IBM, formalized through the CPN partnership, spans several decades.

Ten years ago Rugar collaborated with mechanical engineering Professor Thomas Kenny to develop the process for making ultrasensitive cantilevers. The cantilevers used in the MRFM machine were produced at the Stanford Nanofabrication Facility.

Further, Rugar obtained his doctorate at Stanford many years ago under Calvin Quate, a research professor of electrical engineering.

"The whole field of doing microscopy by measuring forces evolved from an early collaboration between an IBM'er [Nobel Prize winner Gerd Binnig] and a Stanford professor [Quate]," said Rugar. "In some ways we are continuing their legacy."