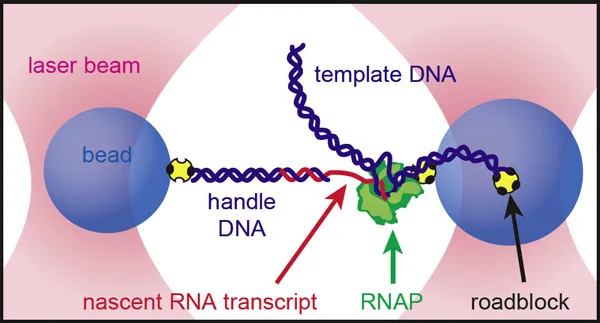

Graphic by Kirsten Frieda and Steven Block: The researchers kept the growing RNA strand taut in a "dumbbell" setup. Two beads were held in place by optical traps. The enzyme that transcribes DNA into RNA - RNAP in the diagram - was attached to one bead, while the new RNA transcript was attached to the other.

Stanford Report - October 19, 2012 - by Max McClure

In a soundproofed, vibration-stabilized, temperature-controlled room, Stanford biophysicist Steven Block was watching a very small origami project.

"The apparatus is so sensitive that, if you talk in the room, the vibrations in the air disturb the movement you're trying to measure," he said quietly. On a black-and-white monitor, two microscopic plastic beads were being slowly drawn apart.

Although we couldn't see it even at this high level of magnification, between the beads was stretched a single strand of RNA, folding up in real time.

Using optical tweezers and sub-nanoscale precision, Steven Block and Kirsten Frieda follow the process – and the consequences – of RNA folding.

Because RNA nucleotides are so small – each is only nanometers long – these effects had never been directly observed before. The Block Lab apparatus is so precise, it can measure distances to within the diameter of a hydrogen atom.

But Block's feat isn't remarkable only for its sensitivity. How RNA molecules fold is a longstanding biological problem. It's crucial for the molecules' function, and different RNA configurations play a fundamental regulatory role during the transcription of those very RNA molecules.

"Issues of gene control are arguably more important than the genes themselves," Block said. "What differentiates organisms are not the genes per se, it's which genes get expressed where and when."

Block, a professor of applied physics and of biology, and graduate student Kirsten Frieda published their findings today in the journal Science.

The key to the "tour-de-force of instrumentation," as Block punned, was the use of "optical tweezers." When placed in the path of a highly focused laser, the team's tiny beads were attracted to the center of the beam, where the electric field produced by the light is strongest. The researchers were thereby able to position and immobilize the beads with extreme consistency and accuracy.

In Block's elegant setup, a single molecule of RNA polymerase – the enzyme that transcribes DNA strands into RNA – was attached to one bead, while the emerging RNA transcript was linked to the other.

By keeping the tension between the two beads constant and measuring the distance between them as they moved apart, Block was able to gauge the changing length of the new RNA strand.

"What we got was a blow-by-blow readout of how RNA folds as it is processed by RNA polymerase," said Block.

In the case of the RNA transcript studied by Block and Frieda, there were two conformation options, which led to two very different functional results.

The "favored" option – about 10 billion times more likely to form, all things being equal – was a terminator structure that would stop transcription if it formed.

The other structure was an anti-terminator formed by an RNA element known as a riboswitch located a little upstream of the terminator. Riboswitches are a common but poorly understood method of gene regulation, found in all kingdoms of life. These stretches of RNA transcripts change conformation after binding certain small target molecules, with consequences for gene control.

The anti-terminator was less thermodynamically stable than the terminator, and therefore much less likely to form. Because it formed slightly more quickly than the terminator, however, "it got its foot in the door," said Block.

"It's a bit like the old joke about escaping a bear in the woods," he said. "You don't actually have to run more quickly than the bear, you just have to run faster than your friend who's with you."

When the riboswitch's target molecule was present, the researchers found, the anti-terminator would consistently form, preventing the terminator from folding and allowing transcription to continue onward. The anti-terminator would only hold its shape for a second or so, but a second is just long enough.

"We were the first to actually see a riboswitch switch," Block said.

The team hopes to extend its techniques to other structured RNAs, including more riboswitches, as well as ribozymes – RNAs that can catalyze chemical reactions – and the tRNAs crucial to protein translation.