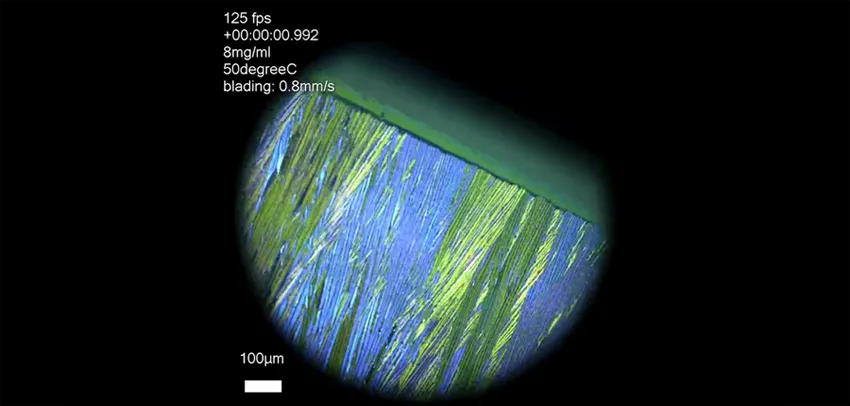

Crystal ribbons forming as the solution is spread using a squeegee-like technique - from video by Gaurav Giri.

Stanford Report, April 18th, 2014 - by Tom Abate

Sometimes engineers invent something before they fully comprehend why it works. To understand the "why," they must often create new tools and techniques in a virtuous cycle that improves the original invention while also advancing basic scientific knowledge.

Such was the case about two years ago, when Stanford engineers discovered how to make a more efficient type of "strained organic semiconductors" that carry currents faster – a big step toward producing flexible electronic devices that couldn't be built using rigid silicon chips.

Stanford scientists help create a novel way to do time-lapse studies of crystallization that will lead to more flexible and effective electronic displays, circuits and pharmaceutical drugs.

Stanford chemical engineering Professor Zhenan Bao and her team discovered how to control the process through which those organic molecules assembled and crystallized as the liquid evaporated. Their findings are described in a recent Nature Communications study.

Bao and her team wanted to understand why their process created such an electronically useful crystal lattice. So they launched a new experiment with help from organic thin film characterization expert Aram Amassian, an assistant professor at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, or KAUST, in Saudi Arabia.

The process of crystallization normally occurs in the blink of an eye and the researchers needed to understand it at the nanoscale. To do this they had to create a way to record and visualize molecules as they formed crystals in slow motion.

In the report, Bao and Amassian reveal how they accomplished this feat: They combined a tiny, bright X-ray beam produced by the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source, or CHESS, in Ithaca, N.Y., with high-speed X-ray cameras to shoot a movie showing how organic molecules form different types of ordered structures or crystals.

The paper explains why the Stanford process can produce such an ideal lattice – quick-evaporation of the solution coupled with the thinness of the liquid were part of the trick, but more surprises were in store. The researchers showed that once the liquid film becomes thin enough, also known as the confinement regime, the type of crystal can be selected with unprecedented control.

Photo by L.A. Cicero: Chemical engineering Professor Zhenan Bao and her

team created a new way to study and control the process of crystallization.

In a more far-reaching sense, the experiments reveal new ways to study and control crystallization, both of which will benefit other fields, such as pharmaceutical manufacturing, where the potency of pills can depend upon precisely controlling the crystal structure of active ingredients.

The team first reported its new process for making fast organic semiconductors in the journal Nature in December 2011. In that paper, the Stanford engineers described how they applied a thin layer of solution to a heated surface.

The solution contained organic semiconductor molecules that evaporated out of the solution and allowed the semiconductor to crystalize into a layer of crystals that could be used to make electronic circuits. They used a technique known as solution shearing to drag the thin layer of liquid across the surface, similar to how a window-cleaner uses a squeegee to clean glass.

In that first paper, Bao's team worked with Stefan Mannsfeld, a staff scientist at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource. He used X-ray scattering to reveal how the molecules in the crystalline layer lined up in a lattice that expedited electron flow.

But the Stanford engineers could not explain precisely why solution shearing packed the crystals into this beneficial structure, or polymorph. "We thought that understanding the mystery could lead to new developments and applications of our method," said Bao.

To accomplish their goal, the researchers had to understand how the molecules formed into a crystal as the solution evaporated.

They had some of the instrumentation required for the task. X-rays can reveal how molecules pack in a crystal much as dental X-rays can disclose the outlines of our teeth.

But teeth stay still during X-rays. Crystals grow and change rapidly. These crystals formed in milliseconds.

One key challenge was to record X-ray images of the molecular crystallization during the squeegee-like process. Amassian and his team had to build a miniature squeegee that could be remotely operated in the safety of the X-ray hutch. The goal was to integrate the solution-shearing setup into the system. The team had previously demonstrated X-ray movies of crystallization working with scientists at CHESS.

To capture the growth process, the researchers used very bright X-rays produced by the synchrotron. They focused the synchrotron beam on a very small spot at the edge of the squeegee blade and fired it at intervals a few milliseconds apart as the squeegee dragged the thinning liquid until crystallization started.

Using a high speed X-ray camera, they took snapshots of the molecular outlines revealed by the beam. Then they reassembled these snapshots to create an animated movie about the process of crystallization.

This had never been done before.

Watching the movies, the scientists found crystals forming in a highly unusual sequence. Crystals can take different forms. These are called polymorphs. The common form of any crystal is usually the most stable and should form last in a sequence of polymorph crystallization. But that was not the case with the crystals that were formed by the squeegee effect. The stable form appeared first at the air-liquid boundary, followed by other polymorphs.

The scientists confirmed their hypothesis by tuning the confinement conditions – thinning or thickening the liquid – to produce different polymorphisms. They discovered that solvents with different molecular sizes affected the formation of polymorphs.

The research may help create strained organic semiconductors for use in electronic devices. It could also yield benefits beyond electronics and in other fields that require precise control over crystal polymorphism. Many drugs, for instance, are made from small molecules that must crystallize in just the right way to have the proper effect.