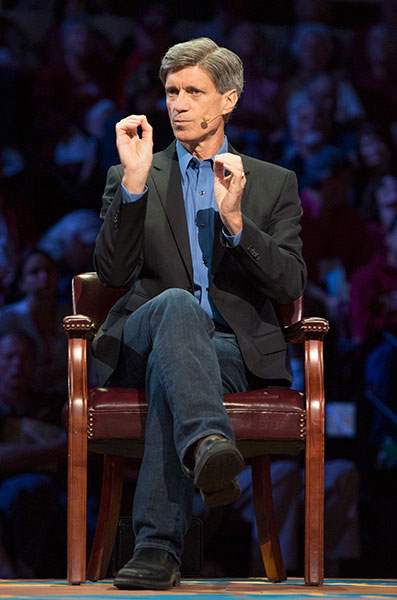

Photo by L.A. Cicero: The 2012 Roundtable at Stanford, 'Gray Matters: Your brain, your life, and brain science in the 21st century,' took place at Maples Pavilion on Saturday. ABC News' Juju Chang moderated the event.

Stanford Report - October 6, 2012 - by Bjorn Carey

The human brain is an amazing machine, easily the most complex computer on the planet. It can learn any language at an early age and, in time, it can find creative ways to rewire its neural connections to recover from a massive injury.

But as remarkable as the brain is, we still know little about how it actually does any of these things. We're still at a loss for how to help a grandmother suffering from Alzheimer's remember her grandchildren.

However, among the speakers at the "Gray Matters" 2012 Roundtable discussion at Stanford on Saturday, there was an encouraging sense that we're nearing the threshold of understanding those mysteries. Experimental drugs are helping mice with Alzheimer's learn and remember new experiences. Scientists are discovering what strengthens developing neural pathways in children.

New brain research will change the way we think, interact and plan throughout our lives. 2012 Roundtable experts talk about how we can apply the new brain science to our own lives, and how neuroscience in the 21st century will affect us all.

"Neuroscience is a priority at Stanford, and we see this as the great new frontier for research," said Stanford President John Hennessy. With faculty in the School of Medicine studying brain biology, engineers inventing new therapeutic devices and the law and economics faculty investigating how and why people make decisions, Stanford's interdisciplinary nature puts it in good position to advance understanding of the brain.

Moderated by ABC News' Juju Chang, a 1987 Stanford graduate, the panel included Carla Shatz, a professor of biology and neurobiology and director of Stanford's Bio-X program; Dr. Frank Longo, the chair of the Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences; Jill Bolte Taylor, a neuroanatomist who specializes in post mortem investigations of the brain; Bob Woodruff of ABC News, who suffered a traumatic brain injury while reporting from Iraq; and John Hennessy.

A main focus of neuroscience is discovering and developing therapies and cures for losses in cognitive ability, whether they be from aging, diseases such as Alzheimer's or traumatic brain injuries. Learning how the brain naturally develops could help illuminate those fixes.

Humans start out life as citizens of the world, Shatz said, able to learn to speak several languages without an accent. Early experiences create connections in the brain, but those connections live and die by the "use it or lose it" rule: As part of normal development, the brain prunes unused connections, to make those that are used more frequently function more efficiently. This is also true not only for languages, but for other abilities as well, such as motor skills and music aptitude.

If we can understand the process that lets us lose connections in early life, we might learn how to improve function of the aging brain, or treat Alzheimer's. "Wouldn't it be nice if you could take a pill and allow your brain to revert to that early learning period?" Shatz said.

Photo by L.A. Cicero: Panelists Dr. Carla Shatz and Bob Woodruff.

Some of the mechanisms that could make such a miracle possible are becoming clear, Longo said. For example, a protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is known to be critical in forming and maintaining synapses – the connections between brain cells – and is active in areas of the brain that play significant roles in learning, memory and high-level thinking. Scientists now know that BDNF levels decrease with aging, and in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. But, they have also found that BDNF levels increase with exercise.

"I don't want to say that we have exercise in a bottle, but this could be an incredibly potent treatment for promoting plasticity, for forming new connections and maintaining the connections that we already have," Longo said.

Relaxing through meditation can suppress the stress circuitry in your brain that can inhibit the formation of new neural connections. And focusing your attention in this way can promote the stabilization of new memories. Taylor emphasized the importance of getting plenty of sleep, which research has shown allows time for your brain to strengthen the new connections and memories it formed during the day.

And what about those popular brain-exercising video games? Longo noted that these games might help you get better at a specific task, but they don't appear to be a cure-all. It's unclear if the gains from these games will spill over to other parts of the brain and help you remember where you parked your car.

Photo by L.A. Cicero: Panelists Jill Bolte Taylor and Preisdent John Hennessy.

Instead, you need to diversify your brain activities. Older citizens tend to try to simplify their lives, Taylor said, but this tells the brain that it doesn't need to handle complicated matters. To stay sharp and maintain neural connections, you need to exercise those connections. The old standby, the crossword puzzle, is good, she said, because it involves interpreting language and society, and that helps you make new associations.

"I encourage everybody to flip your calendar upside down," she said. "You can still figure it out, but you have to work a little."

One of the challenges of treating Alzheimer's is that no one has ever recovered from the disease, making it difficult to gauge what its victims are experiencing. Woodruff and Taylor, having recovered from a traumatic brain injury and a massive stroke, respectively, offer a glimpse of the frustration and fear that Alzheimer's patients might experience, and how to provide comfort to these people.

"Not many of us can say what it would be like to have Alzehimer's," Woodruff said. "I couldn't remember the names of my children, or a single state in the country." He still experiences difficulty recalling certain words, and his laser-like ability to focus on a single task is long gone.

For him, engaging in everyday tasks was more valuable than traditional therapy.

"There's no scientific proof, but I think absolutely that helped speed up the recovery of my brain," Woodruff said.

Taylor's stroke, she said, reduced the Harvard neuroscientist to a helpless infant.

"I felt like an alien in a place that was dangerous. But people who came to me and looked me in the eye, touched me gently and drew me out – that made all the difference," Taylor said.

She now advises the same compassionate approach to people who are trying to connect to loved ones suffering from dementia or Alzheimer's, particularly those who might be closed off to normal routes of communication.

When someone says that he is having trouble connecting with his grandmother suffering from Alzheimer's, Taylor suggests cozying up next to her and giving her a little hug or nudge, and maybe a grunt. "Go into her world. Don't try to get her to understand your reality, go in and be a part of her reality," she said.

The more scientists investigate the brain, the more miraculous and complex it reveals itself to be.

Photo by L.A. Cicero: Panelist Dr. Frank Longo.

"If I had asked my colleagues in computer science 30 years ago, will computers out-think humans by the end of the century, they would have said 'yes.' But we're not even close," Hennessy said.

More studies are needed, and answers might be found in surprising places. Longo noted that in studies in which doctors drilled a hole in into patients' skulls and injected experimental treatments, it was common that even the control group – the patients getting drilled, but injected with a fake treatment – reported improvements. This suggests that the placebo effect, whatever it may be, has some physiological basis and that understanding its mechanism is worth of additional research.

While the progress in neuroscience is promising, fully understanding the brain, and delivering effective treatments, will take time. And money. Shatz pointed out that the significant advances in treating cancer are largely a result of the significant financial investment into research.

For now, the best way to keep your brain in good shape is to do what your mother told you: get exercise, read a book, eat healthy food and go to bed on time.