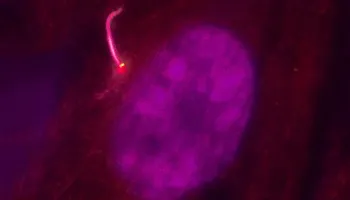

Photo by Tomoharu Kanie and Keene Abbott.

Stanford Medicine Scope - June 21st, 2017 - by Rosanne Spector

In 1675, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, the inventor of the microscope, discovered a tiny antenna that sticks out of our cells. Until the last 20 years this little appendage, called the primary cilium, was largely ignored.

Recently, though, the primary cilium has become the object of fascination for a growing number of scientists intent on figuring out what it does and how it does it. And now professor Peter Jackson, PhD, and his Stanford lab have not only solved one of the thornier mysteries about how it works, they’ve made a discovery they think could help tame the global obesity epidemic.

This might sound far-fetched, but stick with me. First, a little more about the primary cilium: Nearly every cell in your body has one of these structures rising about 2 microns from its surface. It not only looks like an antenna, it also acts like one — but instead of picking up radio signals it picks up chemical signals floating outside of the cell and conveys the information down to the rest of the cell. The antenna’s receivers are various receptor proteins, which cluster at the tip. To get up to the tip, these receptors ride a molecular escalator.

This brings us to the mystery Jackson’s lab solved: How do the right proteins end up inside the cilium to build the escalator and ride it up to the tip? A series of experiments he and his team conducted shows that getting on the escalator is a selective process. They published a report of the experiments last week in the journal Developmental Cell.

“From what we measured in this paper, we realized there are 1,000 people at the bottom but only 15 people on the escalator at the time,” Jackson told me. “It’s like there’s a guy there saying, ‘OK, you can get on,’ to some and ‘don’t even think about it,’ to others.”

It took about a year to figure out what the mechanism was behind the selectivity. With postdoctoral scholar Kanie Tomoharu, PhD, leading the project and technician Keene Abbott running dozens of assays, the team found that two proteins work together to open the way to the cilium: one as a gate and the other as the guard that unlatches it. “If either’s broken, the gate won’t open at all. People just can’t get on the escalator,” said Jackson.

If you want to know the names of the actual protein players: CEP19 is tethered at the base of the cilium by other proteins. (You can think of it as the guard.) RABL2 opens the way to the elevator. (You can think of it as the gate.) When RABL2 binds to CEP19, it admits a protein called IFT-B, which forms the tread of the escalator where riders (such as receptor proteins) stand.

So what does this have to do with obesity?

About 15 years ago, researchers began realizing that various defects in primary cilia resulted in disease, and that several of these diseases had morbid obesity as a symptom. People with Bardet-Biedl syndrome, for example, can weigh as much as 400 pounds because the primary cilium defect that causes the syndrome interferes with the hormonal system in the brain that turns off the urge to eat. “These people keep eating all night long. And there isn’t a drug treatment that can help turn the urge off,” said Jackson, a professor of microbiology and immunology. More recently, researchers have found mutations in the CEP19 genes of certain families with many morbidly obese blood relatives.

So as a starting point in the fight against obesity, Jackson is identifying malfunctioning genes that relate to weight gain and is diagramming their proteins’ interactions. His lab has already found that by analyzing the proteins that interact with primary cilium proteins, they uncover obesity genes to add to the network. His plan is to find what other proteins CEP19 and RABL2 interact with and add their genes too.

“By looking at the extreme cases like Bardet-Biedl, we hope to identify factors that are also altered in more ordinarily obese people. Look at it this way,” he said. “We’ve identified the edge pieces, and now we can build the rest of the puzzle.”