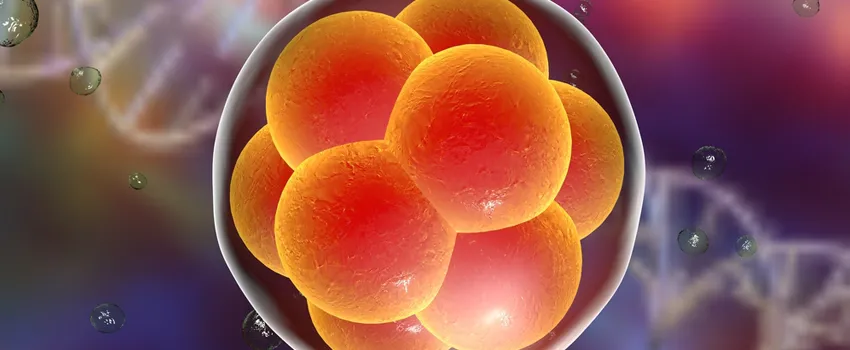

Graphic image by Kateryna Kon, Shutterstock.

Stanford Medicine Scope - July 13th, 2016 - by Krista Conger

The developing human embryo is a thing of mystery and wonder. A hollow ball of cells called a blastocyst, it is as complex and diverse in many ways as our own planet Earth. Across the surface of the sphere, cells pursue their own agendas individually and in tandem. They are orchestrating the patterns of gene expression necessary to launch the three-dimensional developmental programs culminating in a fully formed body with a head and torso, arms and legs, and organs, a spinal cord and a brain — all in the right places. Many mysteries remain because it has been exceptionally difficult to study this process.

Now, Stanford stem cell researcher Vittorio Sebastiano, PhD, and his colleagues have devised a way to study the gene-expression patterns of individual cells to identify regions of the blastocyst that give rise to a structure known as the epiblast that makes the tissues of the embryo. In doing so, they identified developmentally associated changes in the pattern of gene expression across the surface of the blastocyst.

They published their work this week in Developmental Cell.

As Sebastiano explained to me in an email:

In this study we have analyzed the gene-expression profiles of single cells isolated from early- and late-human blastocysts. By doing so we identified a small population of progenitor cells that form in the early blastocyst and constitute the in vivo ‘naive’ cells that give rise to the epiblast in the late blastocyst. Our findings demonstrate how single-cell analysis is instrumental in understanding cellular heterogeneity and a powerful way to dissect the fundamental processes of lineage specification in the developing embryo.

The researchers provide an interactive map of their findings, which is immensely fun to click through (click on the “Instructions and Disclaimer” link for a guide). They also identify a combination of three genes that together can maintain pluripotency, a term used to describe the ability of a cell to become any cell type, in human embryonic stem cells growing in the laboratory. Finally, they also predict that their findings may be useful for the field of in vitro fertilization, as physicians attempt to identify which embryos are likely to thrive after implantation.

As Sebastiano explained:

We have developed the first in silico model of the developing human embryo that we hope will help identifying the molecular signature instrumental to successful development of human embryos, including those obtained by Assisted Reproductive Technology. I and others predict that ART will be the elective method of reproduction of the human species in the future. Therefore, it is fundamental to understand how we form and develop from the very first day of our life.