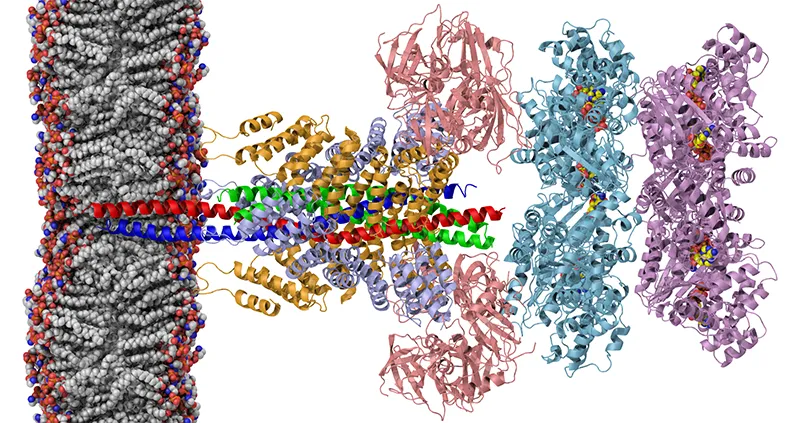

Image courtesy of the Brunger lab.

Stanford Medicine Scope - January 12th, 2015 - by Bruce Goldman

Axel Brunger, PhD, professor and chair of Stanford’s Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology , and a team composed of several Stanford colleagues and UCSF scientists including Yifan Cheng, PhD, have moved neuroscience a step forward with a close-up inspection of a brain-wide nano-recycling operation.

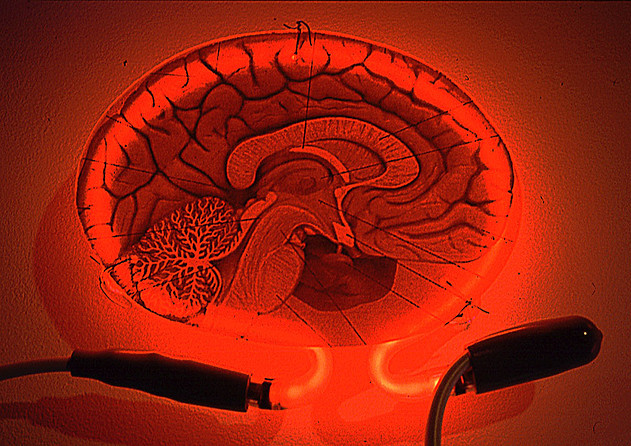

A healthy adult brain accounts for about 2 percent of a healthy person’s weight, and it consumes about 20 percent of all the energy that person’s body uses. That’s a lot of sugar getting burned up in your head, and here’s why: Incessant chit-chat throughout the brain’s staggeringly complex circuitry. A single nerve cell (of the brain’s estimated 100 billion) may communicate directly with as many as a million others, with the median in the vicinity of 10,000.

To transmit signals to one another, nerve cells release specialized chemicals called neurotransmitters into small gaps called synapses that separate one nerve cell in a circuit from the next. The firing patterns of our synapses underwrite our consciousness, emotions and behavior. The simple act of tasting a doughnut requires millions of simultaneous and precise synaptic firing events throughout the brain and, in turn, precisely coordinated timing of neurotransmitter release.

Photo by Carolyn Speranza

You’d better believe these chemicals don’t just ooze out of nerve cells at random. Prior to their release, they’re sequestered within membrane-bound packets, or vesicles, inside the cells. Every time a nerve cell transmits a signal to the next one – which can be more than 100 times a second – hundreds of tiny chemical-packed vesicles approach the edge of the first nerve cell and fuse with its outer membrane, like a small bubble merging with a larger one surrounding it. At just the right time, numerous vesicles’ stored contents spill out into the synapse, to be quickly taken up by receptors dotting the nearby edge of the nerve cell on the synapse’s far side, where, like little electronic ones and zeroes in a computer circuit, they may either trigger or impede the firing of an impulse along that next nerve cell.

Each instance of bubble-like fusion – and this happens not only in neurotransmitter release but in hormone secretion and other processes throughout the body – is carefully managed by a complex of interconnecting proteins, collectively known as the SNARE complex. The molecular equivalent of a clamp, the SNARE complex guides the vesicle ever nearer to the nerve-cell’s surface and then, at just the right moment, squishes it up against the cell’s outer membrane. The vesicle bursts, spilling its contents into the synapse.

Myriad repetitions of this process typify the average day in the life of the average nerve cell. This requires not only a ton of energy (which I guess is where the doughnut comes in) but ultra-efficient recycling. The entire SNARE complex must be constantly disassembled, then reassembled. In a new study in Nature, Brunger and his associates snagged a set of near-atomic-scale snapshots of the SNARE complex as well as the molecular machinery that recycles its components, allowing them to make sophisticated guesses about how the whole thing works. (See the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s news release on the study here.)

This has been a long time coming. In fact, Brunger’s lab first determined the molecular structure of the SNARE complex, via X-ray crystallography, in 1998. The careful decades-long process of tracking down the SNARE complex’s components and their interactions won Stanford neuroscientist Tom Sudhof, MD, the 2013 Nobel Prize in Medicine. But despite its immense importance, you probably haven’t heard much about it. Studies of molecular structures are in general opaque to lay readers, complicated systems such as the SNARE complex all the more so. The popular press pays attention to the awarding of the Nobel, but seldom to the long, towering staircase of incremental discoveries that was climbed to earn it.