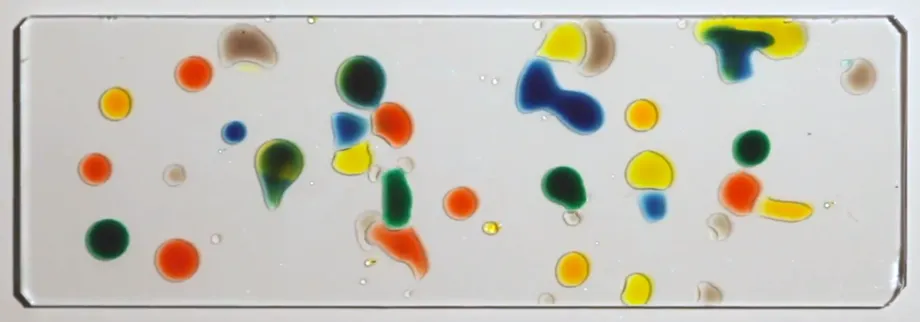

Screenshot from video by Kurt Hickman: Curious about some odd behavior by droplets of food coloring, a trio of Stanford bioengineers discovered the physics that enables certain fluid mixtures to sense one another and move in a molecular minuet.

Stanford Report - March 11th, 2015 - by Tom Abate

A puzzling observation, pursued through hundreds of experiments, has led Stanford researchers to a simple yet profound discovery: Under certain circumstances, droplets of fluid will move like performers in a dance choreographed by molecular physics.

"These droplets sense one another, they move and interact, almost like living cells," said Manu Prakash, an assistant professor of bioengineering and senior author of an article published in Nature.

The unexpected findings may prove useful in semiconductor manufacturing and self-cleaning solar panels, but what truly excites Prakash is that the discovery resulted from years of persistent effort to satisfy a scientific curiosity.

The research began in 2009 when Nate Cira, then an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin, was doing an unrelated experiment. In the course of that experiment Cira deposited several droplets of food coloring onto a sterilized glass slide and was astonished when they began to move.

Cira replicated and studied this phenomenon alone for two years until he became a graduate student at Stanford, where he shared this curious observation with Prakash. The professor soon became hooked by the puzzle, and recruited a third member to the team: Adrien Benusiglio, a postdoctoral scholar in the Prakash Lab.

Together they spent three years performing increasingly refined experiments to learn how these tiny droplets of food coloring sense one another and move. In living cells these processes of sensing and motility are known as chemotaxis.

"We've discovered how droplets can exhibit behaviors akin to artificial chemotaxis," Prakash said.

As the Nature article explains, the critical fact was that food coloring is a two-component fluid. In such fluids, two different chemical compounds coexist while retaining separate molecular identities

The droplets in this experiment consisted of two molecular compounds found naturally in food coloring: water and propylene glycol.

The researchers discovered how the dynamic interactions of these two molecular components enabled inanimate droplets to mimic some of the behaviors of living cells.

Surface tension and evaporation

Essentially, the droplets danced because of a delicate balance between surface tension and evaporation.

Evaporation is easily understood. On the surface of any liquid, some molecules convert to a gaseous state and float away.

Surface tension is what causes liquids to bead up. It arises from how tightly the molecules in a liquid bind together.

Water evaporates more quickly than propylene glycol. Water also has a higher surface tension. These differences create a tornado-like flow inside the droplets, which not only allows them to move but also allows a single droplet to sense its neighbors.

To understand the molecular forces involved, imagine shrinking down to size and diving inside a droplet.

There, water and propylene glycol molecules try to remain evenly distributed but differences in evaporation and surface tension create turmoil within the droplet.

On the curved dome of each droplet, water molecules become gaseous and float away faster than their evaporation-averse propylene glycol neighbors.

This evaporation happens more readily on the thin lower edges of the domed droplet, leaving excess of propylene glycol there. Meanwhile, the peak of the dome has a higher concentration of water.

The water at the top exerts its higher surface tension to pull the droplet tight so it doesn't flatten out. This tugging causes a tumbling molecular motion inside the droplet. Thus surface tension gets the droplet ready to roll.

Evaporation determines the direction of that motion. Each droplet sends aloft gaseous molecules of water like a radially emanating signal announcing the exact location of any given droplet. The droplets converge where the signal is strongest.

So evaporation provided the sensing mechanism and surface tension the pull to move droplets together in what seemed to the eye to be a careful dance.

Rule for two-component fluids

The researchers experimented with varied proportions of water and propylene glycol. Droplets that were 1 percent propylene glycol (PG) to 99 percent water exhibited much the same behavior as droplets that were two-thirds PG to just one-third water.

Based on these experiments the paper describes a "universal rule" to identify any two-component fluids that will demonstrate sensing and motility.

Adding colors to the mixtures made it easier to tell how the droplets of different concentrations behaved and created some visually striking results.

In one experiment, a droplet with more propylene glycol seems to chase a droplet with more water. In actuality, the droplet with more water exerts a higher surface tension tug, pulling the propylene droplet along.

In another experiment, researchers showed how physically separated droplets could align themselves using ever-so-slight signals of evaporation.

In a third experiment they used Sharpie pens to draw black lines on glass slides. The lines changed the surface of the slide and created a series of catch basins. The researchers filled each basin with fluids of different concentrations to create a self-sorting mechanism. Droplets bounced from reservoir to reservoir until they sensed the fluid that matched their concentration and merged with that pool.

What started as a curiosity-driven project may also have many practical implications.

The deep physical understanding of two component fluids allows the researchers to predict which fluids and surfaces will show these unusual effects. The effect is present on a large number of common surfaces and can be replicated with a number of chemical compounds.

"If necessity is the mother of invention, then curiosity is the father," Prakash observed.