Dr. Michael Fischbach is the Liu (Liao) Family Professor of Bioengineering at Stanford University, an Institute Scholar of Stanford ChEM-H, and the director of the Stanford Microbiome Therapies Initiative. Fischbach is a recipient of the NIH Director's Pioneer and New Innovator Awards, an HHMI-Simons Faculty Scholars Award, a Fellowship for Science and Engineering from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation, a Medical Research Award from the W.M. Keck Foundation, a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease award, and the Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship. His laboratory studies the mechanisms of microbiome-host interactions. Fischbach received his Ph.D. as a John and Fannie Hertz Foundation Fellow in chemistry from Harvard in 2007, where he studied the role of iron acquisition in bacterial pathogenesis and the biosynthesis of antibiotics. After two years as an independent fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Fischbach joined the faculty at UCSF, where he founded his lab before moving to Stanford in 2017. Fischbach is a co-founder of Kelonia and Revolution Medicines, a member of the scientific advisory boards of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, and TCG Labs/Soleil Labs, and an innovation partner at The Column Group.

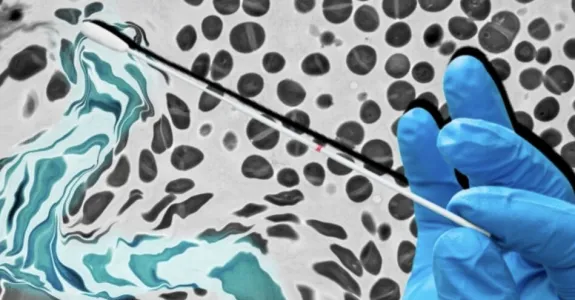

The microbiome carries out extraordinary feats of biology: it produces hundreds of molecules, many of which impact host physiology; modulates immune function potently and specifically; self-organizes biogeographically; and exhibits profound stability in the face of perturbations. The Fischbach lab studies the mechanisms of microbiome-host interactions. Their approach is based on two technologies they recently developed: a complex (119-member) defined gut community that serves as an analytically manageable but biologically relevant system for experimentation, and new genetic systems for common species from the microbiome. Using these systems, the lab investigates mechanisms at the community level and the strain level.

1) Community-level mechanisms. A typical gut microbiome consists of 200-250 bacterial species that span >6 orders of magnitude in relative abundance. As a system, these bacteria carry out extraordinary feats of metabolite consumption and production, elicit a variety of specific immune cell populations, self-organize geographically and metabolically, and exhibit profound resilience against a wide range of perturbations. Yet remarkably little is known about how the community functions as a system. The lab is exploring this by asking two broad questions: How do groups of organisms work together to influence immune function? What are the mechanisms that govern metabolism and ecology at the 100+ strain scale? Their goal is to learn rules that will enable us to design communities that solve specific therapeutic problems.

2) Strain-level mechanisms. Even though gut and skin colonists live in communities, individual strains can have an extraordinary impact on host biology. The lab focuses on two broad (and partially overlapping) categories:

Immune modulation: Can we redirect colonist-specific T cells against an antigen of interest by expressing it on the surface of a bacterium? How do skin colonists induce high levels of Staphylococcus-specific antibodies in mice and humans?

Abundant microbiome-derived molecules: By constructing single-strain/single-gene knockouts in a complex defined community, they will ask: What are the effects of bacterially produced molecules on host metabolism and immunology? Can the molecular output of low-abundance organisms impact host physiology?

3) Cell and gene therapy. They have begun two new efforts in mammalian cell and gene therapies. First, they are developing methods that enable cell-type specific delivery of genome editing payloads in vivo. They are especially interested in delivery vehicles that are customizable and easy to manufacture. Second, they have begun a comprehensive genome mining effort with an emphasis on understudied or entirely novel enzyme systems with utility in mammalian genome editing.