Dr. Lucy O'Brien's Lab studies the behaviors of stem cells and their mature progeny to understand how organs remodel and renew.

Animals live in dynamic environments where external conditions vary at cyclic or irregular intervals. When faced with environmental change, an individual’s physiological fitness requires that its organ systems functionally adapt. One type of organ adaptation occurs through tissue growth and shrinkage, tuning an organ's functional capacity to meet variable levels of physiologic demand. An “economy of nature", adaptive remodeling breaks the allometry of the body plan that was established during development. Unlike embryonic growth, adult organ remodeling is reversible and repeatable, suggesting that it occurs through different mechanisms. Stem cells are key players in at least some of these mechanisms. But, basic questions remain largely unanswered: How do stem cells sense different levels of functional demand? How do they help translate this information into appropriate changes in organ size?

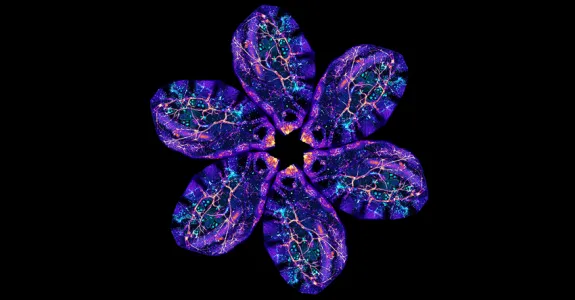

The O'Brien lab has developed the Drosophila midgut as a simple invertebrate model to uncover the rules that govern adaptive remodeling. In adult flies, the midgut is a stem cell-based organ analogous to the vertebrate small intestine. They have found that when dietary load increases, midgut stem cells activate a reversible growth program that increases total intestinal cell number and digestive capacity. The midgut is a uniquely tractable model to study adaptive growth; not only can gene expression be manipulated and lineages traced at single-cell and whole-tissue levels, but complete population counts of all cell types are possible. The lab's goal is to understand how this nutrient-driven mechanism regulates stem cell behavior for lifelong optimization of organ form and function.